170,000 years ago, caverns had spatial planning.

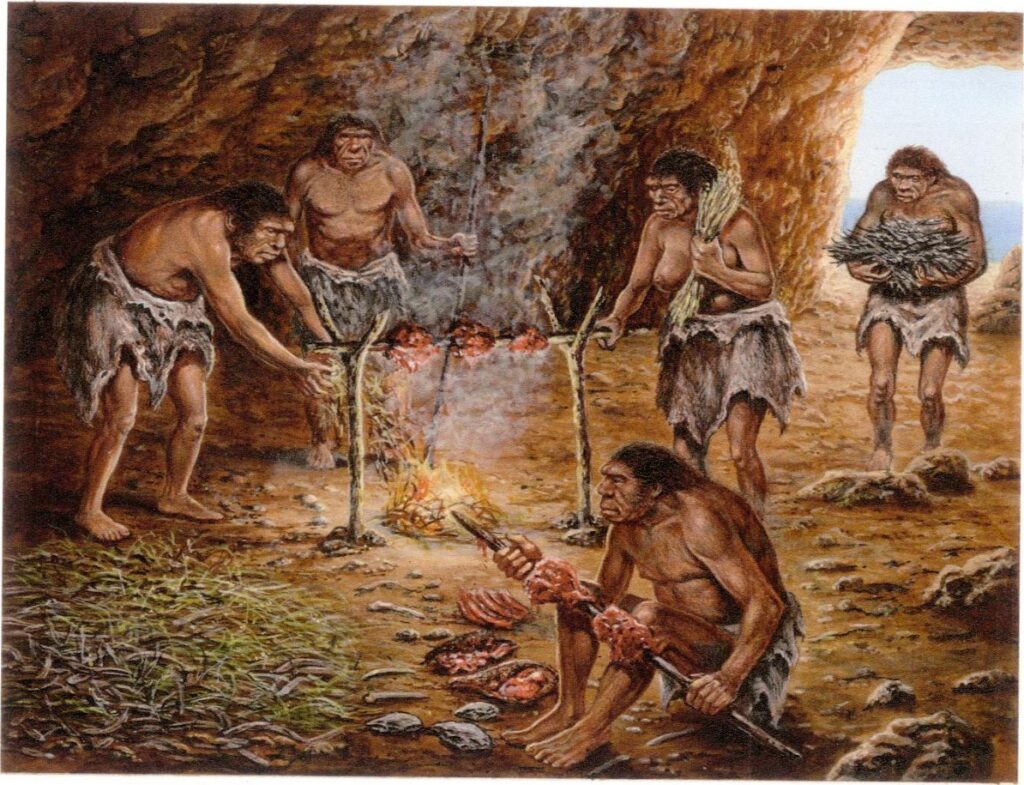

Human ancestors knew a lot about spatial planning, according to the findings: they knew how to control fire and use it for various purposes, and they knew where to put their hearth in the cave to get the most advantage while being exposed to the least amount of hazardous smoke.

They discovered that the cave’s early inhabitants had put their hearth in the ideal location, allowing them to make the most of the fire for their activities and needs while exposing them to the lowest number of smoke.

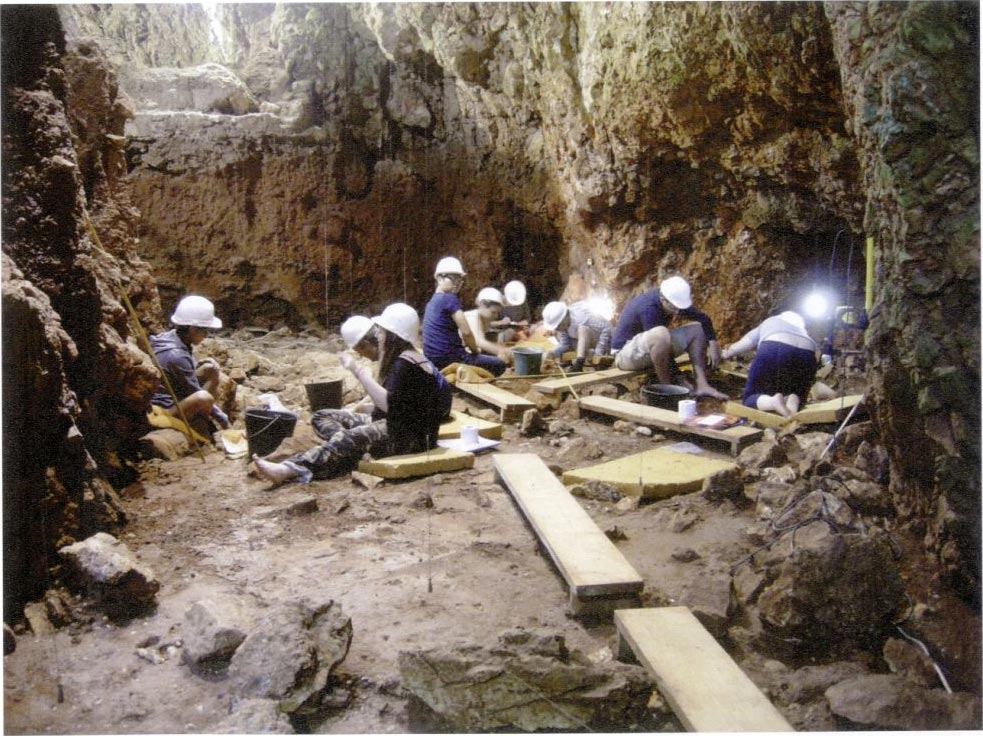

Yafit Kedar, a Ph.D. student, and Prof. Ran Barkai of TAU’s Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures, along with Dr. Gil Kedar, led the research. The research was released in the scientific journal Scientific Reports.

According to Yafit Kedar, the use of fire by early people has been the subject of much dispute among scientists for many years, with questions such as: When did learning occur to manage fire and ignite it at will? When did they start using it regularly? Did they make effective use of the cave’s interior area concerning the fire? While all scholars believe that contemporary humans are capable of all of these tasks, the debate over the capabilities and abilities of previous human species persists.

“The location of hearths in caves occupied by early people for lengthy periods is one focus topic in the argument,” says Yafit Kedar.

The researchers used their smoke dispersion model on a well-studied prehistoric site in southeastern France, the Lazaret Cave, which was inhabited by early people around 170-150 thousand years ago.

“According to our model, which is based on prior studies, positioning the fire towards the back of the cave would have decreased smoke density to a minimum, allowing smoke to circulate out of the cave exactly next to the roof,” says Yafit Kedar.

The hearth, however, was found in the cave’s center in the archaeological layers we analyzed. We tried to figure out why the occupants chose this location and whether smoke dispersion played a role in the cave’s spatial segmentation into activity zones.”

The researchers used a variety of smoke dispersion simulations for 16 possible hearth positions inside the 290sqm cave to answer these concerns. They used hundreds of simulated sensors positioned 50cm beside the floor to a height of 1.5m to measure smoke density throughout the cave for each imagined hearth.

Measurements were matched to the World Health Organization’s average smoke exposure recommendations to better understand the health implications of smoke exposure.

For every hearth, four action zones were mapped in the cave: a red zone that is largely from our boundaries due to high smoke opacity; a yellow zone that is suitable for short-term invasion of a few minutes; a green zone that is suitable for long-term occupation of several hours or days; and a blue zone that is essentially smoke-free.

Early people required a balance – a nearby hearth where they could work, cook, eat, sleep, gather, warm themselves, and so on while being exposed to the least amount of smoke possible. Finally, after weighing all demands – daily activities vs. the dangers of smoke exposure – the cave’s residents chose the best location for their hearth.”

The study determined that a 25-square-meter space in the cave would be ideal for locating the hearth to reap its advantages while avoiding excessive smoke exposure. Surprisingly, the early humans did place their hearth within this location in the several levels analyzed in this study.

“Our work reveals that early people were able to determine the optimal position for their hearth and control the cave’s space as early as 170,000 years ago – much before the arrival of modern humans in Europe,” Prof. Barkai adds. This capacity is the result of ingenuity, experience, and planned activities, as well as knowledge of the health risks associated with smoke exposure. Furthermore, the simulation model we created can help archaeologists excavate new sites by allowing them to seek for hearths and activity zones in the best locations.”