In 2003, an enormous library with 84,000 scrolls was discovered hidden in a wall at the Sakya Monastery in Tibet. It is believed that they had been preserved in their original state for hundreds of years, and it is anticipated that they may contain Buddhist scriptures in addition to works of literature, history, astronomy, and mathematics.

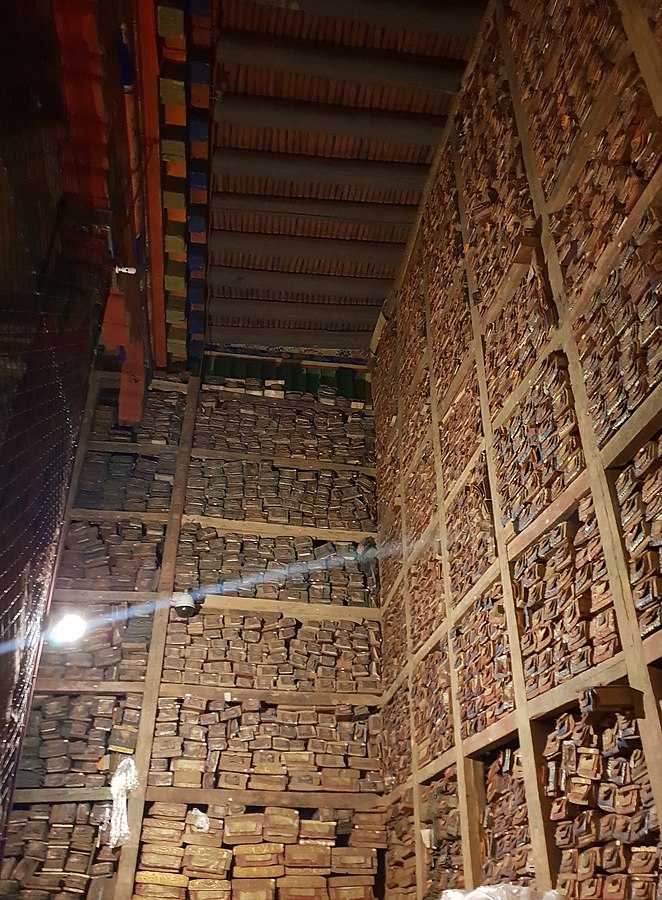

The Library of Sakya Monastery was discovered in southern Tibet, hidden in a nearly 60-meter-long and 10-meter-high wall. It is located in southern Tibet, was constructed in the 13th CE, and is considered to be one of the largest collections of Tibetan and Indic manuscripts in block printed books, containing the history of humanity. It is thought to shed light on the thousands of years of human history.

The Palden Sakya Monastery was established in 1073 in the Tsang district of Central Tibet by Konchog Gyalpo (1034 -1102), who was a member of the Kon (‘Khon) family. The name of the monastery, and by extension, the tradition that he established, was taken from the hue of the soil that was found at its location. The name “Sakya” directly translates to “gray earth.” (Source)

During the Chinese Cultural Revolution, the Sakya Monastery suffered relatively minimal damage, and as a result, its large library was one of the fortunate few that was able to survive the destruction. However, there has been a significant reduction in the amount of time spent studying and practicing in the monastery. At the Sakya College located in Rajpur, Himachal Pradesh, India, the traditions that were started at the Sakya Monastery have been kept alive.

The Main Assembly Hall Lhakhang Chenmo (founded in 1268) is an impressive structure with 16-meter-high walls, and the only ancient building not destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Thick walls (3.5 meters thick) support the building, along with huge sacred pillars. Along the hall’s walls, there is a large statue of Buddhas. These statues contain relics of Sakya abbots. The Buddha in the center contains relics of the founder of the monastery. From the Assembly hall, you can access the Sakya library. There are forty pillars in the Main Assembly Hall, four of which are over one meter in diameter. Each of these 4 pillars has its own name, corresponding to its history: the yellow pillar, the tiger pillar, the wild yak pillar, and the black blood-dripping pillar.

In addition to works of literature, these ancient Tibetan scrolls include various topics such as history, philosophy, astronomy, mathematics, and art. They have been inscribed in gold characters and kept in a great number of volumes. The length of each page is six feet, and the width is eighteen inches. Illuminations can be found in the page margins of each volume, and the illustrations of the thousand Buddhas can be found in the first four volumes.

It is believed that these volumes, which are bound in iron, have been preserved in their original state for hundreds of years. There is a widespread belief that the library at Sakya Monastery is identical to the Apostolic Library that can be found in the Vatican, as well as with underground bunkers with plenty of art. Such an astounding archive of tomes coupled with a colossal collection of artifacts has earned the monastery the nickname the “Second Dunhuang” in reference to the city in the northwest.

Scholar of Tibetan language Das Sharat Chandra writes: As to the great library of Sakya, it is on shelves along the walls of the great hall of the Lhakhang chen-po. There are preserved here many volumes written in gold letters; the pages are six feet long by eighteen inches in breadth. In the margin of each page are illuminations, and the first four volumes have in them pictures of the thousand Buddhas. These books are bound in iron. They were prepared under orders of the Emperor Kublai Khan, and presented to the Phagpa lama on his second visit to Beijing.

There is also preserved in this temple a conch shell with whorls turning from left to right [in Tibetan, Ya chyü dungkar ], a present from Kublai to Phagpa. It is only blown by the lamas when the request is accompanied by a present of seven ounces of silver; but to blow it, or have it blown, is held to be an act of great merit.”

Gansu Province in China ishome to a number of grottoes that are known for their Buddhist murals and manuscripts. A cord can be found that leads to the main prayer hall after passing through a tunnel lined on both sides with copper prayer wheels and going through the massive entryway to the complex. Tibetan prayer flags with their five characteristic colors (blue, white, red, green, and yellow) are wrapped around a pole, while traditional motifs support the brightly painted walls.

Meanwhile, your auditory senses are treated to a mishmash of sounds that blend together harmoniously chanting monks, chattering visitors, and cooing pigeons flapping their wings. Most people in this life will never get to see these invaluable ancient texts or even hear about them. The towering walls might have guarded the temple as one century gave in to the next, but the artifacts have not been as immune. The digital era, however, has thrown a lifeline to the invaluable articles of the Sakya monastery as notebooks and scanners turned obsolete.

An archiving project has been underway since 2015, examining 26 types of ancient artifacts including frescoes porcelain items and instruments. Digitally recording their details gives them a new lease on life in the 21st century. In 2009, in the Indian Himalaya, the world’s most prominent translators, Buddhist scholars, teachers, and volunteers convened for days, sharing decades of research to conclude that only 5% of the Buddha’s teachings had ever been translated into a language spoken today. And in 50 years’ time, there might only remain a handful of people able to understand these ancient languages.

Wonder how much knowledge will be lost if someone destroys this place? Similar incidents already occurred in human history in the distant past when the invaders from Spain destroyed all the sacred books of the Aztecs because they thought it was the devil’s work.