Before Napoleon Bonaparte became Emperor of France in 1804, he brought with him a large number of intellectuals and scientists known as savants,’ as well as army and military personnel from France. In the year 1798, a military expedition in Egypt was launched by these French savants commanded by Napoleon. On the other hand, the involvement of these 165 savants in the French force’s fights and strategy rapidly grew. As a result, a craze known as Egyptomania reignited European interest in ancient Egypt.

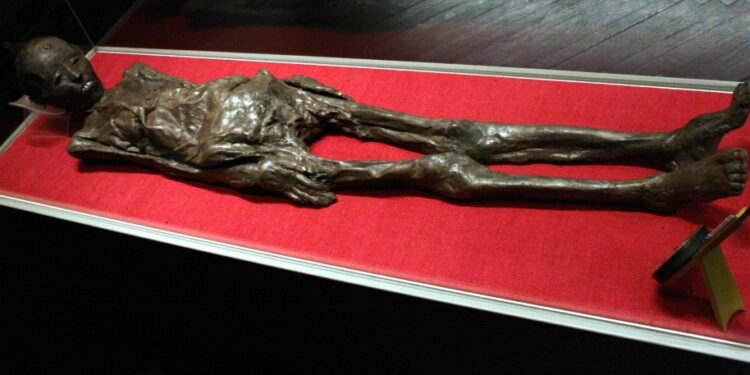

Egyptian artifacts including antique sculptures, papyri, and even mummies were finally transported from the Nile Valley to museums all around Europe. The corpse is known as the Liber Linteus (Latin for “Linen Book”) and its equally famous linen wrappings have finally made their way to the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb, Croatia.

Bari died in 1859, and the mummy was given to his brother Ilija, a priest in Slavonia. The mummy and her linen wrappings were presented to the State Institute of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia (now known as the Archaeological Museum of Zagreb) by Ilija, who had no interest in mummies.

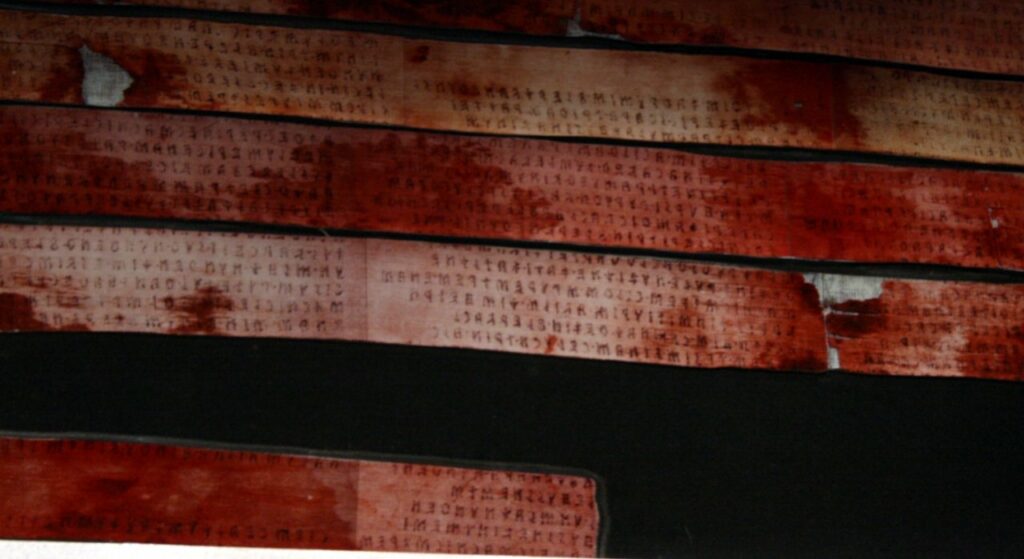

Until then, no one had seen the mysterious writings on the mummy’s wrappings. The writings were uncovered only after German Egyptologist Heinrich Brugsch examined the mummy (in 1867). Brugsch did not explore the topic further, presuming they were Egyptian hieroglyphs.

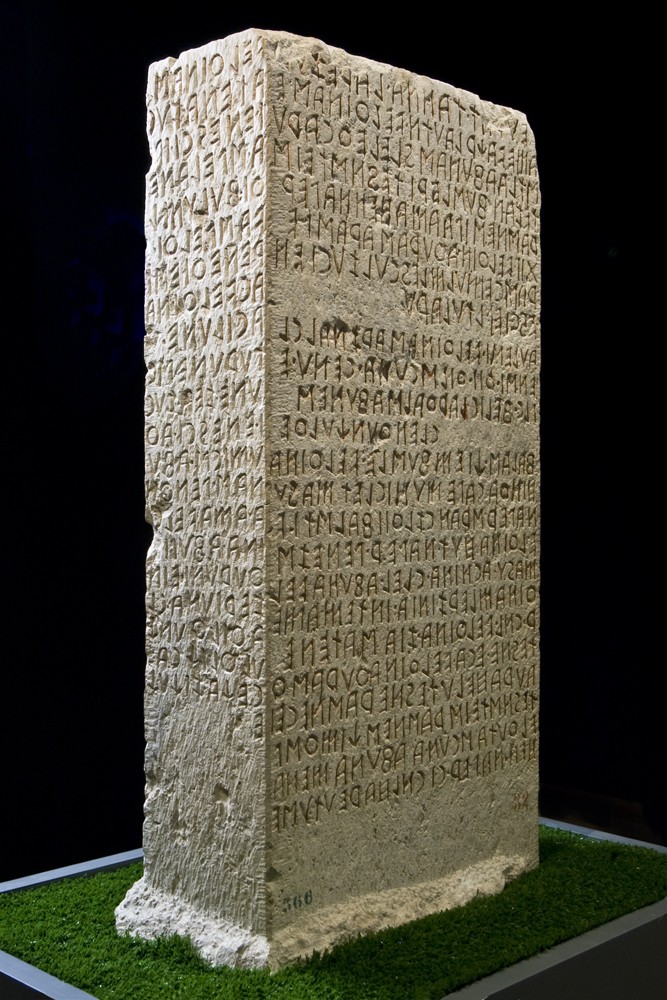

Even though both men understood the importance of the inscriptions, they mistook it for an Arabic translation of the Egyptian Book of the Dead. The inscriptions were later discovered to be written in Etruscan, the ancient Etruscan civilization’s language, in Italy’s ancient area of Etruria (modern Tuscany plus western Umbria and Emilia-Romagna, Veneto, Lombardy, and Campania).

The Etruscan language is still not understood today since so little of the old language has survived. Nonetheless, certain sentences might be utilized to give an idea of Liber Linteus’s subject matter. Based on the dates and god names found throughout the book, the Liber Linteus is thought to have been a religious calendar.

What precisely was an Etruscan book of ceremonies doing on an Egyptian mummy, one would wonder? One possibility is that the deceased was a rich Etruscan who fled to Egypt in the third century BC (the Liber Linteus has been dated to this era) or later when the Romans invaded Etruscan territory.

The scroll identifies the deceased as Nesi-hens, an Egyptian lady who was the wife of Paher-hence, a Theban ‘divine tailor.’ As a result, it’s likely that the Liber Linteus and Nesi-hensu are unconnected, and that the linen used to embalm this Egyptian woman for the afterlife was the only linen accessible to the embalmers.

As a result of this “accident” in history, the Liber Linteus is the oldest known surviving existing text in the Etruscan language.

The Etruscans had a significant effect on early Roman civilization. The Etruscan alphabet, for example, was directly influenced by the Latin alphabet. Architecture, religion, and perhaps even political organization are all examples of this. Though Etruscan had a profound impact on Latin, it was finally eclipsed by it within a few centuries.