Beneath Egypt’s sands lies an ancient enigma, older than the pharaohs or any flood, rising not just from the desert but from the depths of time. The Great Pyramid of Giza, with its intricate chambers and corridors, challenges conventional history. Rather than tombs, some propose these pyramids were power plants—precision-engineered machines defying modern explanation. Incorporating liquid mercury, mica, and massive stones cut with surgical accuracy, they hint at a purpose beyond burial. Theories, like Christopher Dunn’s, suggest the pyramid transmitted microwave signals to satellites, a concept backed by studies of functional devices.

The pyramid’s precision is staggering: aligned to true north within a 360th of a degree, a feat unmatched by many modern structures despite lacking compasses or GPS. Positioned at the geographic center of Earth’s landmass, its 2.3 million limestone and granite blocks, some weighing 80 tons, fit so tightly a razor blade cannot pass between them. Yet, no hieroglyphs or inscriptions mark its interior, undermining claims it was Pharaoh Khufu’s tomb. Its alignment with Orion’s Belt, matching a stellar configuration from 10,450 BC, suggests a timeline far older than Egyptology’s estimates. Curiously, ancient Egyptian records, meticulous in other matters, omit any mention of its construction, hinting it may have been inherited from a lost civilization.

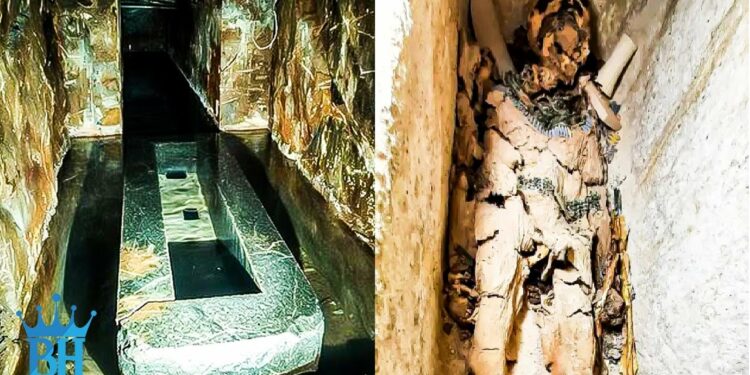

Evidence of advanced machining abounds: basalt blocks bear precise, mechanical saw-like grooves, impossible with bronze chisels, and curved cuts suggest industrial-scale tools. Molten granite ribbons and scorched stones indicate extreme heat, far beyond ancient kilns’ capabilities. Beneath the plateau, the Osiris Shaft plunges 115 feet, housing 30-ton granite and diorite sarcophagi—materials transported impossibly through narrow passages. A man-made canal, still filled with clear water, suggests sophisticated hydrology, not burial rites, but a functional system, possibly for energy or resonance.

At Saqqara’s Serapeum, 70-ton granite boxes, carved from single blocks with laser-like precision, emit resonant tones when struck, suggesting acoustic properties. Their placement in tight tunnels, without soot marks from torches, defies logistical explanation. Edward Kunkel’s 1962 theory posits the pyramid as a hydraulic ram pump, moving water from the Nile or Lake Moeris to support agriculture. John Cadman’s experiments, recreating a pulsating pump with cavitation marks matching the pyramid’s subterranean chamber, suggest it generated vibrations, possibly electricity, via piezoelectric granite and a gold capstone conductor.

Hidden chambers, like the Queen’s Chamber antechamber discovered in 1993, contain copper wiring-like components and circuit-like symbols, sealed deliberately. Sites like Zawyet El Aryan, with granite-lined pits showing water flow, are now inaccessible under military control, fueling speculation of suppressed knowledge. These anomalies—unexplained heat, advanced materials, and silent records—point to a pre-Egyptian civilization mastering vibration, water, and energy. Similar megalithic sites globally, from Peru to Japan, echo this lost knowledge.

The Great Pyramid may not be a tomb but a machine, a memory carved in stone by a forgotten people erased by time. Its secrets, still humming beneath the sands, challenge our history and beckon us to listen, dig deeper, and rediscover a past that waits to be reclaimed.