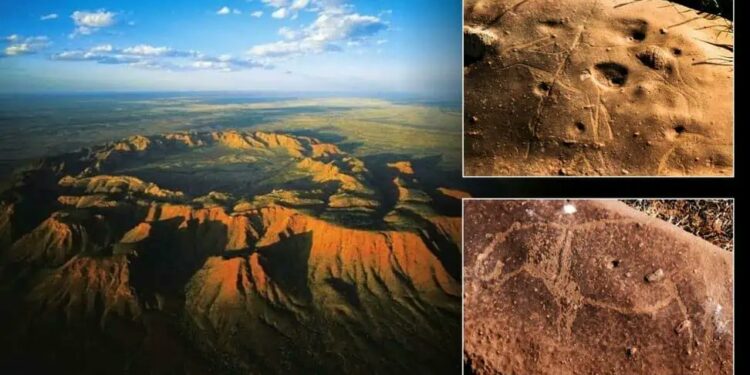

The Vredefort structure, located in South Africa, is famous for its meteorite impact crater, which is the largest in the world. However, this unique location has proven to be more than just an ancient geological site. In a prehistoric discovery that could change our understanding of ancient civilizations, archaeologists in 2019 found 8,000-year-old strange rock carvings made by humans within this world’s largest asteroid impact crater.

These intricate carvings depict various animal species and are believed to have had spiritual significance relating to rainmaking. This discovery sheds new light on the culture and beliefs of the early humans who lived in the region during the Holocene period.

The Vredefort structure is the biggest documented impact crater on Earth, measuring 190 miles (300 km) in width. It was created by an asteroid six to nine miles wide that was moving at about 43,500 miles per hour (70,000 kilometers per hour) when it collided with the Earth during the Paleoproterozoic Era, over 2 billion years ago.

Many studies had already been conducted on the structure of the impact site in the century since its discovery; however, little research had been conducted on some of the crater’s more unusual features, such as its “Granophyre Dykes” – the long, narrow structures that can be six miles long and 16 feet wide. They are made of a brown-grey rock that is full of fragments of various other rocks inside of it.

In the last few decades, the previous works on the dykes established that they formed because of the impact, but it is still uncertain how the molten material from which the rocks were created was carried to the surface.

During their investigation into these peculiar rock formations, the researchers came across a collection of ancient carvings at the site that had previously been unknown to archaeologists.

Matthew T. Huber, senior lecturer in economic geology at the South Africa’s University of the Free State, visited the site in 2010. According to Huber, planetary scientists and geologists working at the location had already known about the rock arts for many years. But when Huber and his team came to learn that the archaeological and anthropological communities were still unaware of the presence of these strange rock arts, they immediately began to seek assistance in further studying these features.

Today, there are multiple “generations” of carvings at the site, spanning from 8,000 years ago to as recently as 500 years ago. In thier research, Huber and his team concluded that the dike was almost certainly used as a rainmaking site, they confirmed it from the petroglyphs that were there.

According to Huber, “The art styles changed through time, and some carvings have been altered (changing the head of an animal to a different animal). However, what remains constant at the site is the connection to rainmaking.”

The carvings, which include what appears to be a hippo, horse, and rhino, were made 8,000 years ago by the Khoi-San – known as South Africa’s ‘First Peoples.’ Scientists today have recognized the special nature of the impact crater, but, according to Huber, it was also recognized by so many ancient inhabitants of the area.

“The area around these Dykes is littered with artifacts and carvings from the Khoi-San people. Obviously, they also recognized the significance of the site. What is amazing is that the same Dykes that we recognize to have the most geological significance also had the most spiritual significance for these early inhabitants. Our anthropological studies are focused on trying to uncover exactly what was done at these sites and how it influenced the people that were there.” — Mathew T. Huber

Researchers further noticed that one of the Dykes resembles the shape of the “Rain Snake” – an important deity at the time.

Archaeologists Shiona Moodley and Jens Kriek, who also worked at the site note that San mythology is split into a three-tiered universe. Above is occupied by god and spirits of the dead, the middle is the material world, while below is associated with the dead and shamanistic travel. Snakes, they said, were found on all three tiers, and they were thought of as creatures of “rain.”

They even note that, according to the Khoi-San beliefs, their uppermost deity “Kaggen” could transform himself into a snake. In this form, he had the power to flood the countryside.

Huber believes the Khoi-San used the snake-shaped dyke as a “rainmaking site.” He said that while some of the art styles and carvings had changed over time, there is a constant connection to rain.

“The dyke is positioned near the Vaal River – a body of water – and is on top of a hill. As a high point, it would have attracted lightning strikes. The animals carved into the dyke are all associated with the rainmaking mythology of the San. All of these features point towards the site being used for making rain.” — Mathew T. Huber

Perhaps we may never know the true meaning of these carvings, but it’s incredible to think that they have survived for so long and continue to teach us about our past, giving us a glimpse into the beliefs and culture of the people who made them. The fact that the carvings depict animals and may have had spiritual significance is truly fascinating.

The discovery is a testament to the boundless possibilities of scientific exploration and the endless mysteries still waiting to be unraveled. We can’t wait to see what else the scientific community will uncover in the future!