Around 2,000 years ago, in a coastal location of Peru that gets less than 4 millimeters of rain per year, an ancient culture emerged around an agrarian economy based on maize, squash, yucca, and other crops. The Nazca Lines, ancient geoglyphs in the desert that range from simple lines to images of monkeys, fish, lizards, and many other strange figures, are the most well-known part of their heritage.

The Nazca people governed the region from 1000 BC until 750 AD. The origins of the aqueducts had been a mystery for decades, but Rosa Lasaponara of the Institute of Methodologies for Environmental Analysis in Italy said that her team had finally cracked the code.

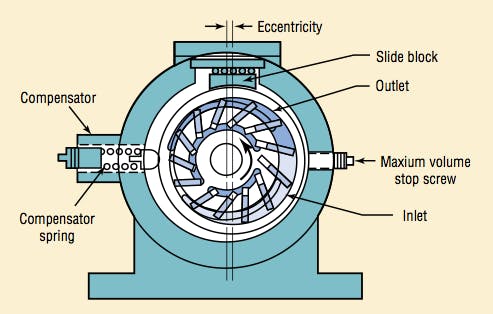

The puquios were later identified as a “complex hydraulic system constructed to draw water from subsurface aquifers” thanks to satellite photos. Rosa Lasaponara believes her find explains how the indigenous Nazca people managed to survive in a water-stressed area. Not only did they survive, but they also developed agriculture.

The puquios are located near the well-known Nazca lines, and the meaning of these ancient holes has been debated extensively. They may have been part of a complex irrigation system, according to certain historians and archaeologists. Others suggested that they were burial grounds for religious rituals.

Using satellite imaging, Lasaponara and her colleagues were able to better understand how the puquios were scattered over the Nazca area, as well as where they ran in relation to nearby communities, which are easier to date.

“What is clear now is that the puquio system had to be far more complicated than it seems now,” Lasaponara continues. “The puquio method helps to expand valley agriculture in one of the world’s most arid locations by exploiting an endless water supply throughout the year.”

Scholars have been unable to determine the origin of the puquios since regular carbon dating processes could not be performed on the tunnels. The Nazca also didn’t leave any clues as to where they originated from. They, like many other South American societies, lacked a writing system, with the notable exception of the Maya.

Lasaponara adds, “What is actually astounding is the vast amount of effort, planning, and collaboration required for their development and continuing upkeep.”

In an area that is one of the driest on the globe, this guaranteed a regular, continuous water supply for decades. To put it another way, the Nazca area’s most comprehensive hydraulic project made water accessible all year, not just for agriculture and irrigation, but also for home purposes.