A lifelike facial approximation of a man who lived 30,000 years ago in what is now Egypt may offer clues about human evolution.

In 1980, archaeologists unearthed the man’s skeletal remains at Nazlet Khater 2, an archaeological site in Egypt’s Nile Valley.

Anthropological analysis revealed that the man was between 17 and 29 years old when he died, stood approximately 5 feet, 3 inches (160 centimeters) tall and was of African ancestry.

However, little else was known about him other than that he was buried alongside a stone ax.

Now, more than 40 years later, a team of Brazilian researchers has created a facial approximation of the man using dozens of digital images they collected while viewing his skeletal remains, which are part of the collection at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

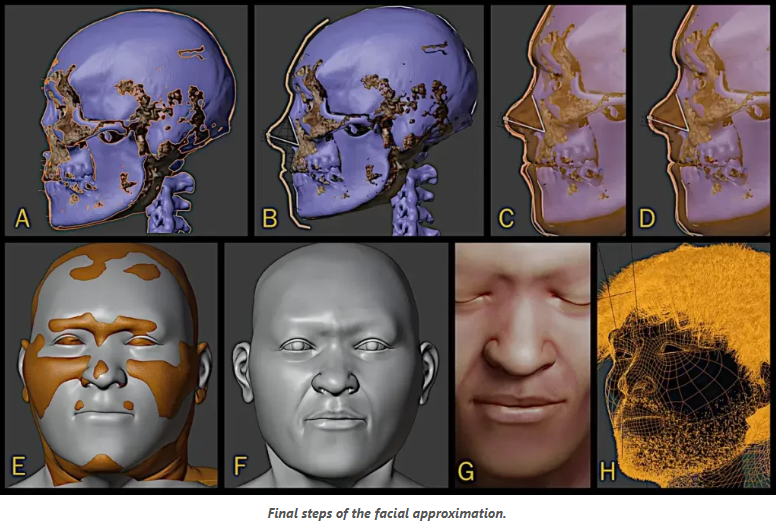

“The skeleton has most of the bones preserved, although there have been some losses, such as the absence of ribs, hands, [the] middle-inferior part of the right tibia [shin bone] and [the] lower part of the left tibia, as well as the feet,” first author Moacir Elias Santos, an archaeologist with the Ciro Flamarion Cardoso Archaeology Museum in Brazil, told Live Science in an email. “But the main structure for facial approximation, the skull, was well preserved.”

One characteristic of the skull that stood out to the researchers was the jaw and how it differed from more modern mandibles.

A portion of the skull was also missing, but the team copied and mirrored it using the opposite side of the skull and used data points from computerized tomography (CT) scans from living virtual donors.

“The skull, in general terms, has a modern structure, but part of it has archaic elements, such as the jaw, which is much more robust than that of modern men,” study co-researcher Cícero Moraes, a Brazilian graphics expert, told Live Science in an email. “When I observed the skull for the first time, I was impressed with that structure and at the same time curious to know how it would look after approaching the face.”

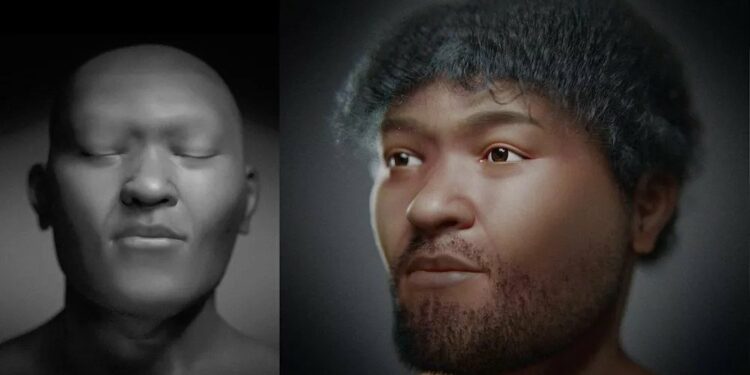

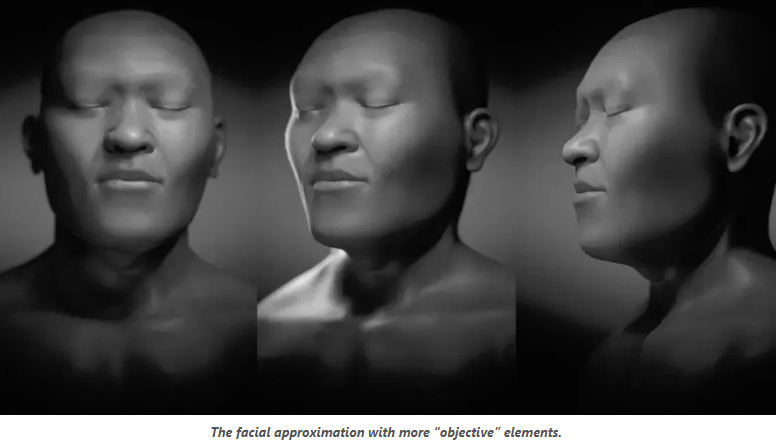

By digitally stitching together the images in a process known as photogrammetry, the researchers created two virtual 3D models of the man.

“In general, people think that facial approximation works like in Hollywood movies, where the end result is 100% compatible with the person in life,” Moraes said. “In reality, it’s not quite like that. What we do is approximate what could be the face, with available statistical data and the resulting work is a very simple structure.

“However, it is always important to humanize the individual’s face when working with historical characters, since, by complementing the structure with hair and colors, the identification with the public will be greater, arousing interest and — who knows — a desire to study more about the specific subject or archeology [and] history as a whole,” he added.

The researchers hope that providing a look at this ancient man could help archaeologists better understand how humans have evolved over time.

“The fact that this individual is over 30,000 years old makes it important for understanding human evolution,” Santos said.