Archaeologists excavating near a Middle Eastern fortress discovered two mass graves holding the gruesome corpses of Christian soldiers defeated during the medieval Crusades. Some of them were possibly buried by a king personally.

Inside the dry moat of the ruins of St. Louis Castle in Sidon, Lebanon, the chipped and burnt bones of at least 25 young men and teenage boys were discovered.

According to radiocarbon dating, they were among the many Europeans who priests and kings persuaded to take up arms in a futile attempt to reclaim the Holy Land between the 11th and 13th centuries.

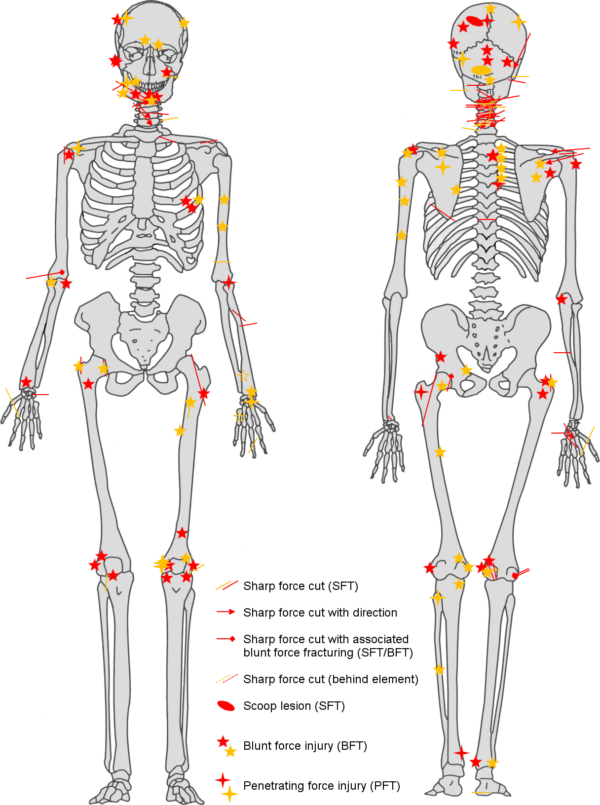

“I knew we had made a significant discovery when we found so many weapon injuries on the bones as we unearthed them,” said Richard Mikulski, an archaeologist at Bournemouth University in the United Kingdom who excavated studied the remains.

The researchers used DNA and naturally existing radioactive isotopes in the men’s teeth to confirm that some of them were born in Europe. An examination of distinct versions, or isotopes, of carbon in their bones indicates that they died in the 13th century. After the First Crusade in 1110, Crusaders took St. Louis Castle for the first time.

A crucial strategic port, the invaders held on to Sidon for more than a century. Still, historical records show that the castle was assaulted and destroyed twice, the first by the Mamluks in 1253 and the second by the Mongols in 1260.

According to the researchers, the troops died “very likely” during one of these fights, and by harsh means, all bones have a stab and slice wounds from swords and axes and indications of blunt-force trauma.

The troops had more wounds on their backs than on their fronts, implying that many were assaulted from behind, probably while fleeing during a rout, and charged them down on horseback, based on the distribution of these hits.

“One individual received so many wounds (a minimum of 12 injuries involving 16 skeletal elements). In which significantly more violent blows were applied than was required to overcome or kill them,” the researchers wrote.

The charring on some bones implies that the men’s bodies were attempted to be burned after their horrible deaths, and then their bodies were left to decompose on the battlefield.

However, after a royal intervention, the dead were swept into a mass grave. According to a belt buckle found among the bones, the soldiers were Frankish and came from a region that encompassed modern-day Belgium and France. Because of their provenance and the period of their death, the soldiers may have been buried by King Louis IX of France.

“Crusader records show that King Louis IX of France was on crusade in the Holy Land at the time of the attack on Sidon in 1253,” said Piers Mitchell, a University of Cambridge anthropologist. The latter served as the project’s Crusades expert. “After the battle, he proceeded to the city and personally assisted in burying the rotting corpses in mass graves like these.” Wouldn’t it be incredible if King Louis himself assisted in the burial of these bodies?”

The French king, who was eventually canonized as a saint, launched two assaults into the Holy Land — the Seventh and Eighth Crusades — after pledging to God that if he were allowed divine assistance in recovering from malaria, he would regain the country.

The archaeologists may never know who killed the soldiers in Sidon and then buried them. Still, their graves provide a rare glimpse into a horrific period that usually is only documented in written texts.

“Thousands of people perished on all sides during the crusades, but archaeologists rarely locate the troops killed in these legendary conflicts,” Mitchell explained. “We can begin to comprehend the awful realities of medieval battle because of the wounds that covered their bodies.”

The findings were published in the journal PLOS ONE on August 6th.