The Babylonian Hanging Gardens ascended to the skies like a mountain. On the uppermost tier, the exotic plants grew luxuriant and tall. This magnificent paradise was dubbed one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World by Greek historians of the Hellenic Age. Six of those wonders are certain to have existed, according to scholars. The famed gardens, on the other hand, have escaped historians for millennia. What happened to them? Did they even exist? One researcher believes she has cracked the code.

Babylon’s Hanging Gardens Have a Legendary Origin

One common mythology about the gardens is that they were erected for King Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605-562 BC) of Babylon’s homesick bride, Amytis of Media. Amytis yearned for Persia’s lush highlands. According to mythology, the garden was located some 50 miles south of Baghdad in what is now Al Hillah, Babil, Iraq. Unfortunately, no documents, inscriptions, or archaeological evidence exist in Babylon to back up this claim.

Gardens on the Move

The Fertile Crescent in Mesopotamia, where Babylon flourished, was a turbulent period in history. Civilizations rose only to fall victim to a more powerful ruler’s merciless conquest. Palaces, temples, documents, and municipal constructions were all destroyed throughout the battles. As a result, all remnants of the Hanging Gardens may have vanished, leaving us with no archaeological proof.

It’s also conceivable that historians erred in their research or made up certain information. To support their purposes, writers frequently blended myths and tales with history or falsified facts. Furthermore, even though ancient writers mentioned spectacular gardens, due to massive text damage, only a few pieces exist.

As a result, tracing the descriptions back to the oldest and, presumably, most reputable sources is difficult. Throughout the years, the existing fragments from which each version was derived became shrouded in various copies of copies. Nonetheless, certain genuine truths may have remained in succeeding authors’ works.

Details of Babylon’s Hanging Gardens

It’s difficult to find the first reliable description of Babylon’s Hanging Garden. Ctesias of Cnidus, who flourished in the fifth century BCE, is thought to be the oldest. Only pieces of his work have remained, none of which relate to the Babylonian Gardens. Diodorus Siculus appears to have followed Ctesias’ account closely, according to plinia.net. As a result, we still have Diodorus’ account of the Babylonian Hanging Gardens.

Scholars think Ctesias credited the garden to Semiramis, the Assyrian regent queen (a.k.a. Sammu Ramat). In the ninth century BCE, she was known for her leadership and numerous improvements to Babylon. Diodorus opposes this by claiming that the gardens were not erected by Semiramis, but rather by a Syrian King who came later.

Details regarding the garden may be found in Diodorus’ Bibliotheca Historica, Book 2 Chapter 10 (perseus.tufts.edu) (in Greek). Plunia.net has a complete translation by Irving Finkel. The following is a condensed version of the description:

The garden was square and had 400-foot-long sides. It featured layers that ascended in height from the bottom terrace to the top terrace, which was 75 feet high – the same height as the city walls. Each layer was supported by 14-foot-long by four-foot-wide stone beams in a vaulted gallery underneath it.

Reeds in thick bitumen cover the beams, and the ceiling is waterproofed with two extra layers of baked bricks bonded together and a coating of lead. A thick layer of earth developed above the foundation, allowing many different sorts of trees to grow, some of which were either stunningly enormous or beautiful. The plentiful water came from the river and flowed up a secret conduit in one of the galleries through a complex mechanical system.

What Other Historians Thought

Clitarchus’ descriptions of Babylonian gardens were used by later writers such as Strabo. Philo of Byzantium offers a similar narrative to the one presented above. He claims, however, that the irrigation originated at a higher elevation and trickled down into the garden. Based on Clitarchus’ work, Quintus Curtius Rufus (first century BCE) described the Hanging Gardens.

Then there’s Berossus, who is sometimes credited with creating the first version. However, his copy does not survive, and it is possible that the following authors embellished Berossus’ work with specifics concerning the garden. Herodotus, on the other hand, wrote about Babylon’s walls, roads, and canals in great detail in the fifth century. Despite this, he forgot to include any gardens.

Despite the jumble of parts, there are certain inscriptions and reliefs from Nineveh, the Neo-Assyrian capital, that describe a remarkable garden. These inscriptions, in combination with archaeological data, point to a large-scale artificial irrigation system.

Nineveh’s Hanging Gardens

Dr. Stephanie Dalley, an Oxford University Assyriologist, can interpret ancient cuneiform inscriptions. She’s suggested a notion that challenges conventional wisdom. The Hanging Gardens of Nineveh, some 340 miles north of Babylon, were built by the Assyrian king Sennacherib (r. 705 BCE to 681 BCE).

Sennacherib’s records include some of the proof for this. In the remains of his palace, archaeologists discovered stone prisms bearing cuneiform inscriptions. Dalley noticed something unusual when she interpreted the cuneiform. The monarch describes the exotic trees and plants in his castle garden. He described how he created a mechanical mechanism that brought water up to the top levels of the garden all day. Dalley says he created a screw similar to Archimedes’.

Sennacherib’s Annals are still alive today in the shape of stone prisms. In her book, The Mystery of Babylon’s Hanging Gardens: A Translation, Dalley includes a translated passage.

I made clay molds for ‘cylinders’ (gimahhu–tall tree trunks) and ‘screws’ (alamittu –palm trees) as if by supernatural knowledge… 4 I had ropes, bronze wire, and bronze chains constructed so that I could pull water all day. 5 In place of a shaduf, I placed ‘cupper’ cylinders and’screws’ above cisterns. Those pavilions came out perfectly. 6 I increased the height of the palace’s environs to make it a wonder for all people. ‘Incomparable Palace’ was the name I gave it.

I constructed a high garden (kirimhu) adjacent to it, emulating the Amanus mountains, with various aromatic plants, orchard fruit trees, trees that fill not only mountain land but also Chaldaea (Babylonia), and trees that bear wool [cotton?].

Irrigation Problems

Scholars think Sennacherib’s garden would have required roughly 300 tons of water every day, according to Dalley. Archaeological evidence, on the other hand, reveals how he irrigated such a vast area.

Sennacherib was the world’s sovereign and the king of Assyria. I had a watercourse directed to the outskirts of Nineveh across a long distance, connecting the waters… I built an aqueduct of white limestone stones that spanned steep-sided valleys and forced the rivers to flow across it.

Sennacherib’s Wall Reliefs in the Gardens

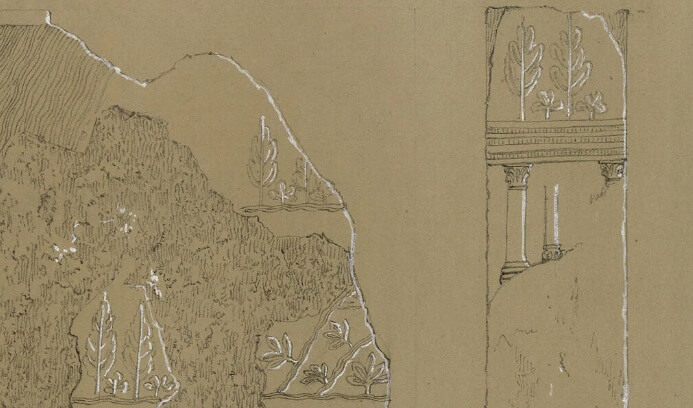

Sennacherib’s triumphs were also memorialized in painted bas-reliefs that adorned his palace. The British Museum’s archives contain an identical drawing of one of his reliefs, which has since been lost. It depicts a multi-leveled garden with an arching aqueduct that supplies the garden with water. Colonnades also support the terrace garden in the top right-hand corner. This seems similar to Diodorus’ description of the 14-foot-long stone beams that support the garden’s several levels.

Examining the Situation

Is it possible that Sennacherib’s Hanging Garden became a World Wonder? Nobody can be certain. Perhaps there were several gardens worth mentioning. After all, Mesopotamia was known for its exquisite gardens. Semiramis, the female queen who subsequently became known as Semiramis, may have created magnificent gardens. During the Hellenic Age, however, writers described the machinery that hoisted water, the rise like a theatre, the stone pillars, and the variety of plants and trees in ways that are similar to Sennacherib’s inscriptions and bas-reliefs: the machinery that hoisted water, the rise like a theatre, the stone pillars, and the variety of plants and trees.

There are additional indications now, according to Dr. Dalley and other archaeologists, that point to the past presence of a wonderful garden, not in Babylon, but Nineveh. We may never know if the Hanging Garden was included in the “Top Seven” list of ancient wonders. However, today’s best evidence leads to Sennacherib’s capital city.