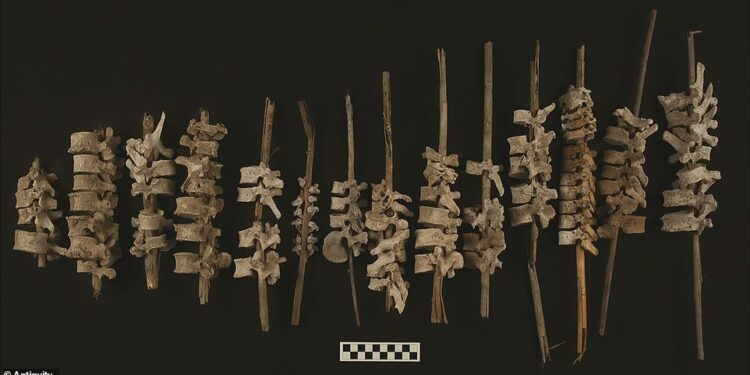

According to researchers, Indigenous people in Peru’s Chincha Valley invented the practice of stacking human vertebral columns to rebuild the bodies of the dead that had been destroyed by Spanish colonists.

Ancient Indigenous communities were able to use sticks to rebuild remains after Spanish pillage destroyed them, according to a study published in the journal Antiquity in February 2022.

The study’s lead author, archeologist Jacob Bongers of the University of East Anglia, commented, “These ‘spine-on-posts’ were presumably created to reconstruct the dead to protest against grave robbery.”

They found that spine-on-posts are direct, ritualized, and indigenous to European colonialism.

Bongers and his colleagues examined 192 vertebrae discovered in the Chincha Valley, which formerly homed to the strong Chincha Kingdom. The majority of the spines were discovered in ancient chullpas (known as graves), which could hold hundreds of people. They found a single person’s spine in all.

Radiocarbon dating reveals a significant gap between when the bones were buried and when they were strung together. The bones date from around 1530 in the early 16th century, but they were put together on sticks nearly 40 years later.

The arrival of the Spanish in Peru, who robbed and destroyed Indigenous graves, corresponds with this time frame.

“In the colonial period, indigenous grave robbery was common over the Chincha Valley,” Bongers noted.

“Firstly, grave robbery aimed at extracting gold and silver from grave goods, and it would have coincided with European efforts to destroy indigenous religious and funeral rites.”

In other words, when plundering the Chincha tombs, Europeans had two objectives. They aimed to recover buried valuables while also destroying indigenous cemeteries and forcing people to follow Christian beliefs.

However, locals fought against it. The complete body after death was crucial to them. And Bongers and his colleagues believe that this prompted them to return to the destroyed graves and begin stringing spines onto posts to rebuild their forefathers’ bodies.

“They’re picking up the remains and attempting to reassemble them. They tried to rebuild the dead.”

He observed that the practice seemed to be widespread.

The Chincha Kingdom governed over the Chincha Valley from 1000 to 1400. It was a “rich, centralized community that ruled Chincha Valley during the Late Intermediate era, which preceded the Incan Empire,” according to Bongers.

The Chincha Kingdom unified the Inca Empire in the 15th century, but it retained some autonomy. However, the arrival of the Europeans destroyed the locals. As a result of starvation and epidemics, the number of heads of households fell from 30,000 to only 979 between 1533 and 1583.

The threaded vertebrae, according to Bongers, represent the violence that residents in the Chincha Valley experienced at the time.

“Ritual is crucial in social and religious life, but it could become a conflict, particularly during the period of conquest when new power was established.” He said. “These discoveries affirm that this conflict occurred at graves.”

Studying graves can reveal how individuals lived, worshipped, suffered, and died.

“Mortuary traditions are arguably what distinguishes us as humans – this is one of the main distinguishing features of our species,” Bongers added. “People express their humanity through mortuary practice.”

After reading about Peruvian spines threaded onto posts, learn about the mummy tied with a rope that archeologists discovered in Cajamarquilla, Peru. Discover how Peruvians came together to rebuild the Q’eswachaka bridge, which had fallen into a river during the epidemic.