Modern science has added a level of sophistication to human history, enabling the treatment of numerous hereditary and acquired impairments. Simple and successful surgical techniques can now be used to fix our eyes and ears. What did prehistoric humans do? Evidence of cranial surgery as far back as 2,000 years has been discovered in Greece and Peru, and one example of trepanation as far back as 11,000 years has been discovered in Turkey. A new stream of evidence from Spain has now been added to the age of surgery. An ear operation was performed on an older woman found in a 5,300year-old Neolithic Spanish tomb, according to a report published in the journal Scientific Reports by researchers from the University of Valladolid, offering the earliest evidence of ear surgery ever.

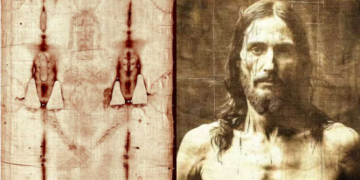

Neolithic ear surgery to relieve aural pain was discovered near the left ear canal of a 5,300year-old skull. According to the Spanish experts, this shows that the ear operation was performed by someone with some “anatomical competence.”

“How much we can say is that certain individual people would have achieved an extent of anatomy experience and knowledge as ‘healers’ or budding physicians, if you like, to succeed in this kind of primitive healing,” said Manuel Rojo-Guerra of the Department of Prehistory and Palaeontology, who has been excavating the site since 2016 with colleagues Sonia Daz-Navarro and Cristina Tejedor-Rodrguez from the University of Valladolid.

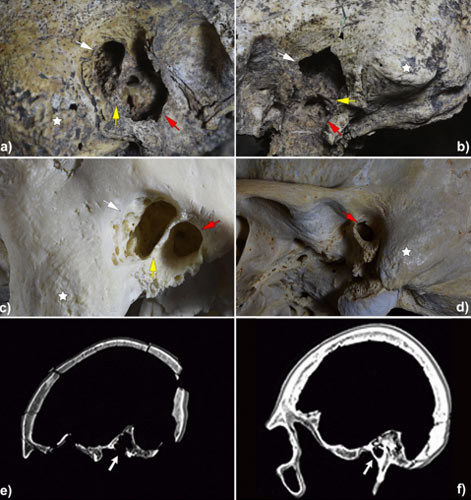

Both ear canals had been surgically changed using trepanation, in which holes were drilled into the skull on either side, an “old-school” method, according to computer tomography scans.

“The theory suggested in this study is that the guy whose skull was found had both ears surgically intervened. “Based on the disparities in bone remodeling between the two temporals, it appears that the treatment was first performed on the right ear, due to an ear pathology sufficiently alarming to necessitate intervention, which this prehistoric woman survived,” the study’s authors stated.

Performing the Procedure

The skull was discovered for the first time in 2018. The researchers concluded that this was “the first known radical mastoidectomy in the history of humankind” because of the drilled burr holes in the temporal lobes.

The tomb also revealed the existence of incredibly sharp flint knives that had been warmed multiple times, as well as evidence of chopped bone. In reality, evidence revealed that some of the blades had been warmed several times to temperatures between 300 and 350 degrees Celsius (572-662 degrees Fahrenheit). These temperatures were established by the absence of fire cracks and other heat treatment signs. As a result, the researchers were able to determine that this was “an actual cautery or surgical device for performing the procedure.”

A Painful and Delicate Relationship

The delicate nature of such a surgical surgery cannot be overstated, especially without the equipment we have today. To determine whether there was an infection in the ear, the “healers” would have to use their naked eye (presuming that the holes were drilled properly in the first place).

Under normal circumstances, the process would have involved “progressive circular and abrasive drilling generating terrible anguish.” To relieve pain and/or lose consciousness, the patient would have to be physically confined by other members of the community or given mood-altering medicines like hallucinogens.

The Dolmen of El Pendón has provided a large amount of bone remains from about 100 people “who suffered from various diseases and traumas,” suggesting that these bones may be evidence of early surgical treatments, many of which failed.