In 2007, archeologists were looking for shipwrecks beneath the waters of Lake Michigan when they came across something far more interesting than they had anticipated. They found a boulder with the prehistoric carving of a mastodon, an elephant-like animal that went extinct about 10,000 years ago, as well as a series of stones arranged in a manner similar to that of Stonehenge. Similar stone alignments have been found throughout England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales.

Marc Holley, who is a professor of underwater archaeology at the Northwestern University of Michigan, and his colleague Brian Abbott are the ones who made the discovery. Holley has participated in underwater archaeology and cultural resource management projects in Michigan since 1995. These projects have included the prediction of prehistoric sites in Saginaw Bay, the archaeological survey of Fayette Harbor, the archaeological survey of the historic shipwreck “New Orleans,” and the development of an archaeological survey plan for historic shipwrecks of both Thunder Bay and Grand Traverse Bay (in northern Michigan).

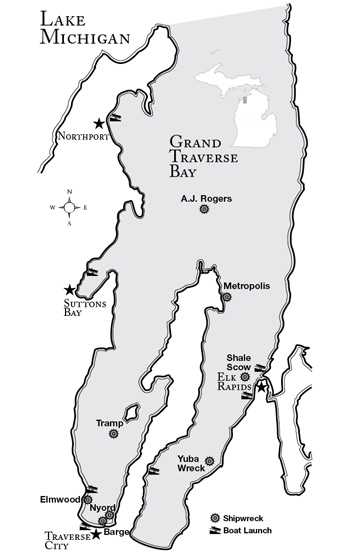

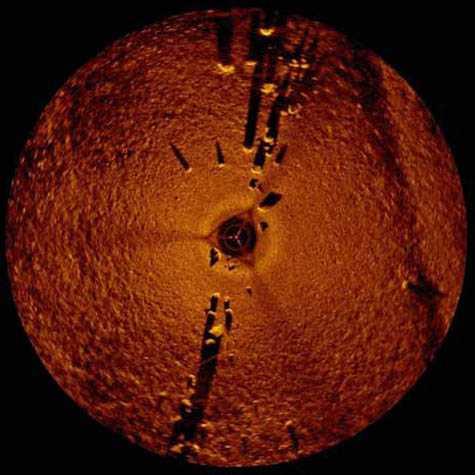

Using sonar techniques to search for shipwrecks at a depth of about 40 feet in Lake Michigan’s Grand Traverse Bay, archaeologists discovered sunken boats, cars, and even a Civil War-era pier. However, they also discovered this prehistoric surprise, which can be deduced from the sonar scan photos. Grand Traverse Bay is located in the northwestern corner of the lower peninsula of Michigan, and the preserve has seven wrecks within its boundaries that are readily accessible from shore and are in relatively shallow depths including the wreck of a sunken Ford Pinto.

The Grand Traverse Bay Underwater Preserve exists because the state of Michigan adopted a novel method of conserving its submerged cultural history for the simple reason that so much cultural heritage is easily available to anyone with a boat and scuba gear in Michigan waters. Because the ships were so easily accessible and well-preserved, they were swiftly looted for their riches and trinkets, thereby degrading them for future divers.

Since shipwrecks were already so well-preserved, a group of concerned divers banded together to preserve them for future generations. Michigan established its underwater preserve system in 1980, six years before the Abandoned Shipwreck Act was passed, making it one of the first states to take an active interest in conserving their undersea heritage. The state of Michigan separated its seas where there was a high concentration of shipwrecks into twelve underwater preserves, each with its own council that is administered by the Michigan Underwater Preserves Council, which also maintains a phone number for reporting artifact theft.

The boulder with markings is approximately 5 feet in length and 3.5 to 4 feet in height. Photos depict a surface that is fractured in a variety of ways. While there is obviously some doubt as to whether or not that really is a mastodon carved on a rock – let alone if it really was human activity that arranged these rocks into a circle – it is worth pointing out that Michigan does already have petroglyph sites and even standing stones.

According to Dr. Holley, the ones that formed what might be a petroglyph stood out the most. Some of them might have a natural origin, while others might have been made by humans. He stated that when taken into consideration as a whole, they give the impression of the outlines of a mastodon-like back, hump, head, trunk, tusk, triangular-shaped ear, and sections of legs. “We couldn’t believe what we were looking at,” said Greg MacMaster, a president of the underwater preserve council.

The experts who were shown photographs of the boulder that had the mastodon marks have requested additional information before determining whether or not the markings are an ancient petroglyph. “They want to actually see it,” he said. Unfortunately, he added, “Experts in petroglyphs generally don’t dive, so we’re running into a little bit of a stumbling block there.”

Is it possible that a Stonehenge-like structure, similar to the one in England, is buried beneath the icy waters of a remote bay in the northern part of Lake Michigan? If this is the case, are there other prehistoric megaliths that have been buried and are just waiting to be found by an intrepid archaeologist armed with a sonar scanner?