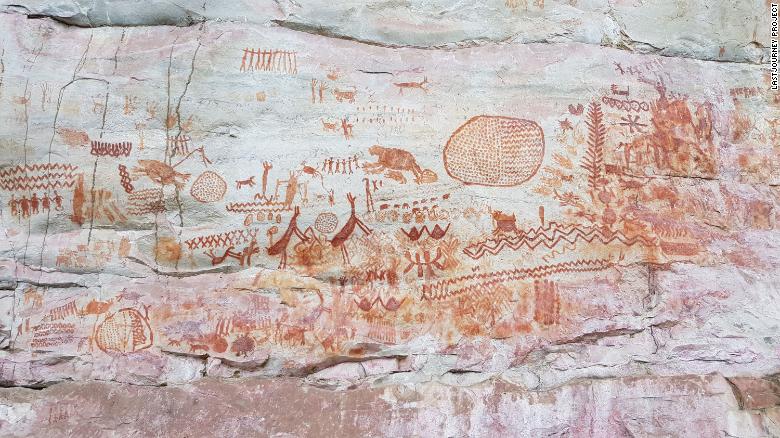

South America was filled with ice age animals more than 12,000 years ago, including car-sized ground sloths, elephantine herbivores, and a deer-like species with an extended snout.

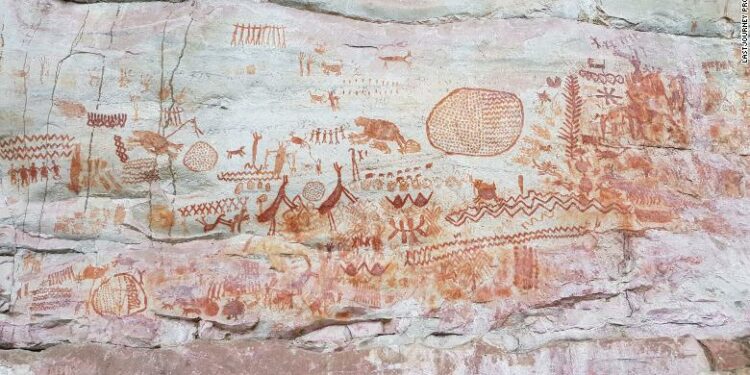

According to a new study, these extinct giants are among many species immortalized in an 8-mile-long (13-kilometer-long) frieze of rock paintings at Serrana de la Lindosa in Colombia’s Amazon jungle – art made by some of the region’s first inhabitants.

The frieze, which was likely painted over decades, if not millennia, is dubbed “the last trip” by Iriarte because it depicts the advent of humanity in South America, the last territory conquered by Homo sapiens as they moved over the world from their origins in Africa.

These northern pioneers would have encountered unusual animals in an unfamiliar environment.

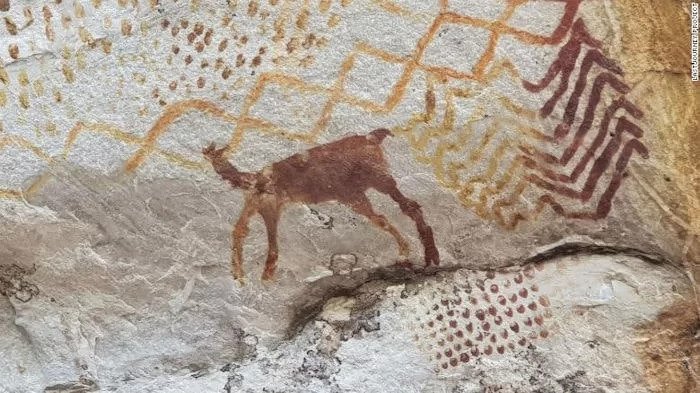

“They came across these large-bodied mammals and painted them.” And, while we don’t have the final say, these paintings are highly naturalistic, with morphological traits of the animals visible,” he remarked.

However, discovering “extinct megafauna” among the dazzlingly beautiful paintings is contentious and debatable.

Other archaeologists believe the paintings’ excellent preservation points to a far more recent origin and that the animals represented maybe anyone.

The vast ground sloth discovered by Iriarte and his colleagues, for example, could be a capybara, a large rodent found throughout the region today.

What’s the last word?

While Iriarte acknowledges that the new research isn’t conclusive in this argument, he is sure that they have discovered evidence of early human contacts with some of the world’s vanishing giants.

Among the five animals identified in the paper are a giant ground sloth with massive claws, a gomphothere (an elephant-like creature with a domed head, flared ears, and a trunk), an extinct lineage of a horse with a thick neck, a camelid like a camel or a llama, and a three-toed ungulate, or hoofed mammal, with a trunk.

While the red pigments used to create the rock art have yet to be dated, Iriarte stated that ocher fragments discovered in layers of sediment during excavations beneath the painted vertical rock walls dated 12,600 years ago.

The goal is to date the red pigment used to paint the miles of rock, but dating cave paintings and rock art is notoriously difficult. Ochre, an inorganic mineral pigment that contains no carbon, cannot be dated using radiocarbon dating.

The archaeologists are hopeful that the ancient artists blended the ocher with a binding agent that would help them determine a precise date. The findings of this probe will most likely be released later this year.