Jewelry has been a symbol of power and status since ancient times. It has served as a currency and a form of trade, as well as a decorative accessory. Queen Hetepheres’ silver bracelets are an excellent example of how jewelry can provide insights into trade networks and the economic and social status of ancient societies.

Egypt has no domestic silver ore sources and silver is rarely found in the Egyptian archaeological record until the Middle Bronze Age. Bracelets found in the tomb of Queen Hetepheres I – mother of King Khufu, builder of the Great Pyramid at Giza (date of reign 2589-2566 BC) – form the largest and most famous collection of silver artifacts from early Egypt.

In new research, scientists from Macquarie University and elsewhere analyzed samples from queen Hetepheres’ bracelets using several state-of-the-art techniques to understand the nature and metallurgical treatment of the metal and identify the possible ore source. Their results indicate that the silver was most likely obtained from the Cyclades (Seriphos, Anafi, or Kea-Kithnos) or perhaps the Lavrion mines in Attica. It excludes Anatolia as the source with a fair degree of certainty.

This new finding demonstrates, for the first time, the potential geographical extent of commodity procurement networks utilized by the Egyptian state during the early Old Kingdom at the height of the Pyramid-building age.

Silver artifacts first appeared in Egypt during the 4th millennium BC but the original source then, and in the 3rd millennium, is unknown. Ancient Egyptian texts don’t mention any local sources, but an older view, derived from the presence of gold in silver objects, plus the high silver content of Egyptian gold and electrum, holds that silver was derived from local sources.

An alternative view is that silver was imported to Egypt, possibly via Byblos on the Lebanese coast, owing to many silver objects found in Byblos tombs from the late fourth millennium.

The tomb of Queen Hetepheres I was discovered at Giza in 1925 by the Harvard University-Museum of Fine Arts joint expedition. Hetepheres was one of Egypt’s most important queens: wife of 4th Dynasty king Sneferu and mother of Khufu, the greatest builders of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686-2180 BC). Her intact sepulcher is the richest known from the period, with many treasures including gilded furniture, gold vessels and jewelry.

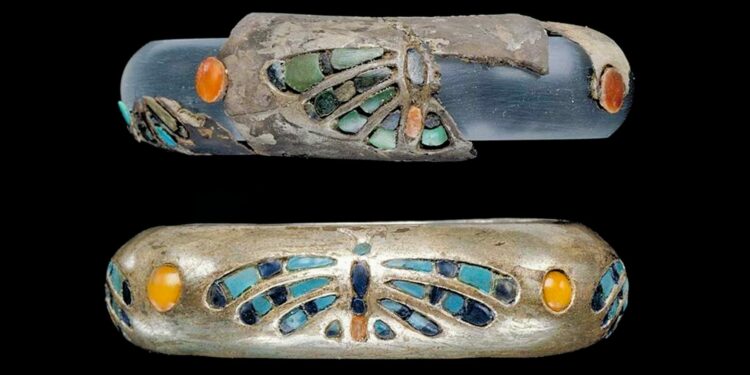

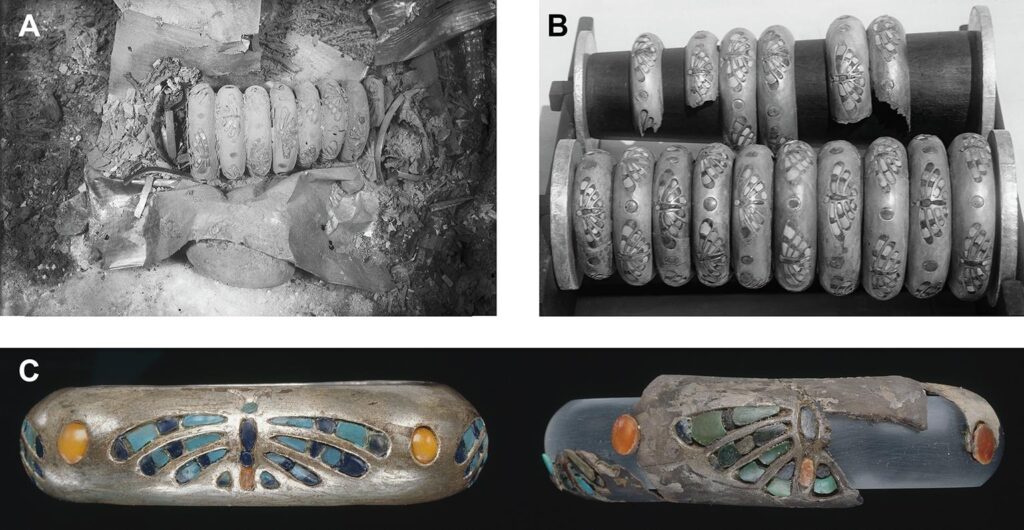

Made of metal rare to Egypt, her bracelets were found surrounded by the remains of a wooden box covered with gold sheeting, bearing the hieroglyphic inscription ‘Box containing deben-rings.’ Twenty deben-rings or bracelets were originally interred, one set of ten for each limb, originally packed inside the box.

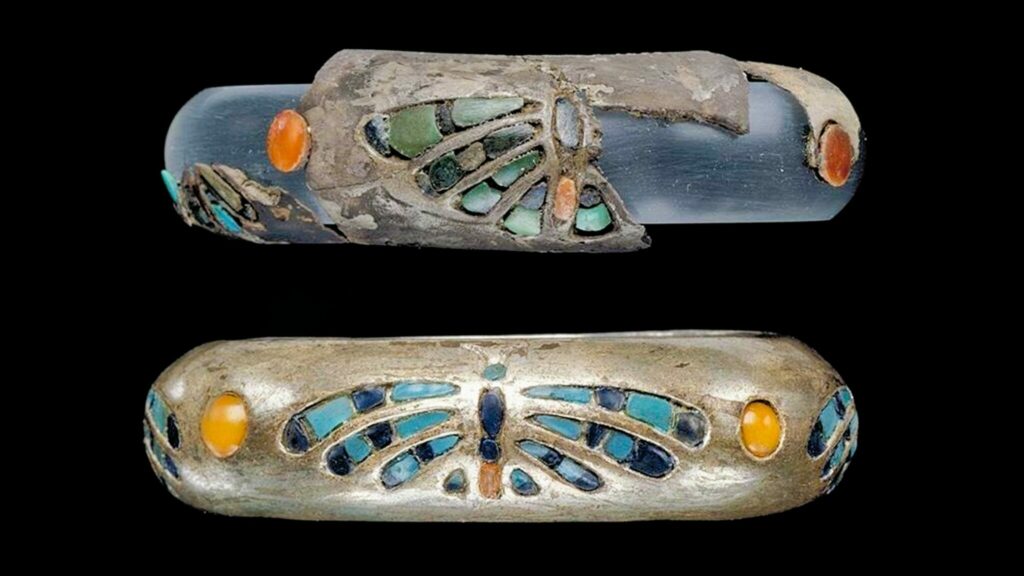

The thin metal worked into a crescent shape and the use of turquoise, lapis lazuli and carnelian inlay, stylistically mark the bracelets as made in Egypt and not elsewhere. Each ring is of diminishing size, made from a thin metal sheet formed around a convex core, creating a hollow cavity on the underside.

Depressions impressed into the exterior received stone inlays forming the shape of butterflies. At least four insects are depicted on each bracelet, rendered using small pieces of turquoise, carnelian and lapis lazuli, with each butterfly separated by a circular piece of carnelian. In several places, pieces of real lapis have been substituted by painted plaster.

“The origin of silver used for artifacts during the third millennium has remained a mystery until now,” said Dr. Karin Sowada, an archaeologist at Macquarie University. “The new finding demonstrates, for the first time, the potential geographical extent of trade networks used by the Egyptian state during the early Old Kingdom at the height of the Pyramid-building age.”

Dr. Sowada and colleagues found that Queen Hetepheres’ bracelets consist of silver with trace copper, gold, lead and other elements. The minerals are silver, silver chloride and a possible trace of copper chloride. Surprisingly, the lead isotope ratios are consistent with ores from the Cyclades (Aegean islands, Greece), and to a lesser extent from Lavrion (Attica, Greece), and not partitioned from gold or electrum as previously surmised.

The silver was likely acquired through the port of Byblos on the Lebanese coast and is the earliest attestation of long-distance exchange activity between Egypt and Greece. The analysis also revealed the methods of early Egyptian silver working for the first time.

“Samples were analyzed from the collection in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the scanning electron microscope images show that the bracelets were made by hammering cold-worked metal with frequent annealing to prevent breakage,” said Professor Damian Gore, an archaeologist at Macquarie University. “The bracelets were also likely to have been alloyed with gold to improve their appearance and ability to be shaped during manufacture.”

“The rarity of these objects is threefold: surviving royal burial deposits from this period are rare; only small quantities of silver survived in the archaeological record until the Middle Bronze Age (c. 1900 BC); and Egypt lacks substantive silver ore deposits,” Dr. Sowada said.