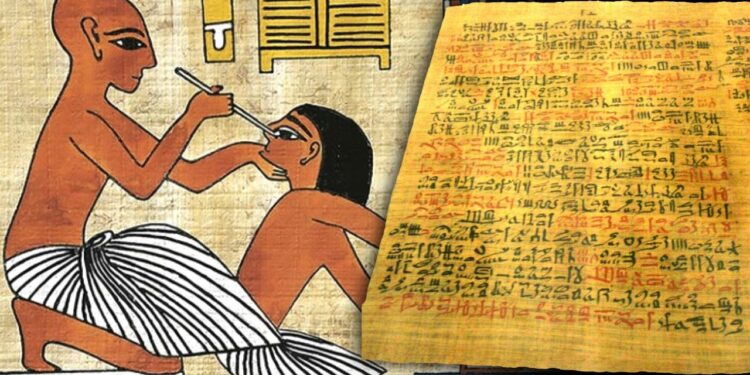

The Ebers Papyrus offers a plethora of medical knowledge and is one of Egypt’s oldest and most complete medical manuscripts.

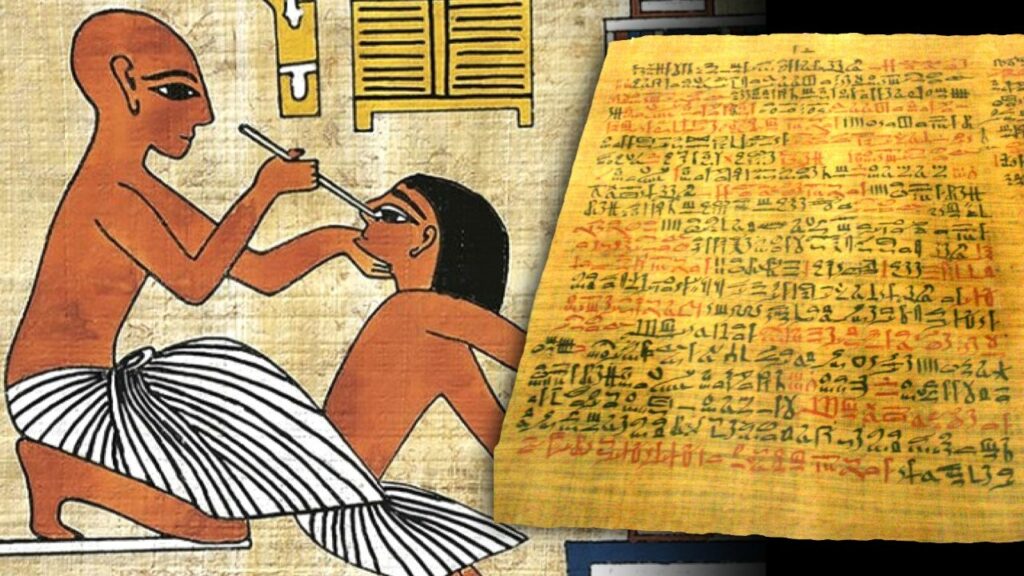

The Ebers Papyrus is an ancient Egyptian medical record with over 842 cures and injuries. It concentrated on the heart, the lungs, and diabetes in particular.

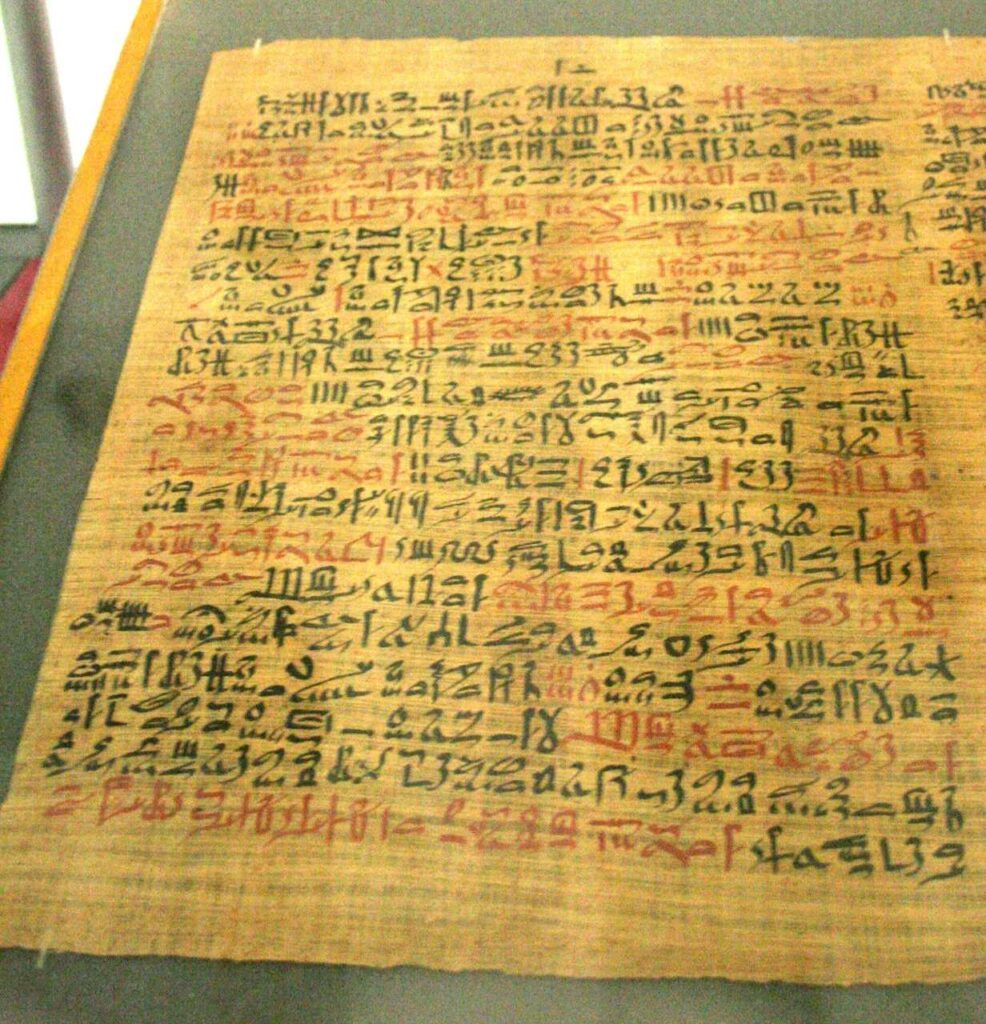

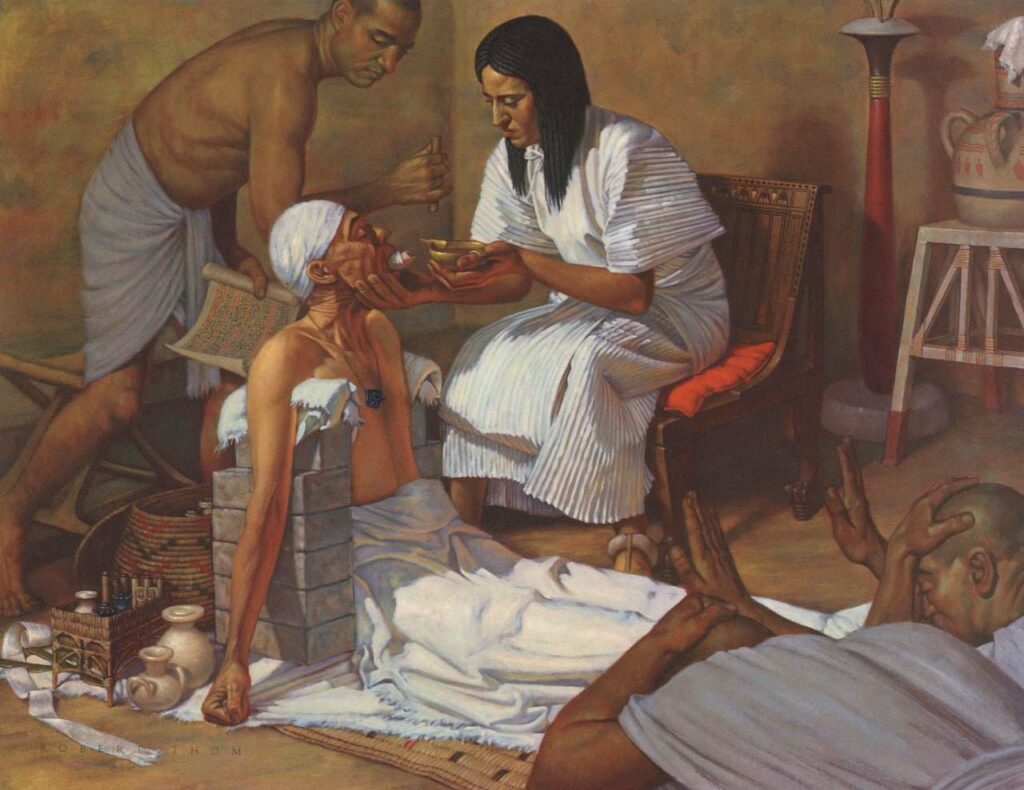

Egypt’s oldest and most extensive medical record is the Ebers Papyrus. It shows a fusion of the scientific (known as the logical approach) and the magical-religious (known as the magical approach) in Ancient Egyptian medicine (known as the irrational method). It has undergone extensive scrutiny and has been re-translated nearly five times and is credited with providing significant insight into Ancient Egypt’s cultural milieu between the 14th and 16th centuries BC.

Even though the Ebers Papyrus includes a wealth of medical knowledge, there is little proof of how it was discovered. Before being purchased by Georg Ebers, it was known as the Assassin Medical Papyrus of Thebes. It’s as enjoyable to understand how it came into Geog Ebers’ hands as it is to hear about the medical and spiritual treatments it addresses.

The Ebers Papyrus’ legend and history

According to folklore, in 1872, Georg Ebers and his wealthy backer Herr Gunther entered a rare collections shop in Luxor (Thebes) run by a collector named Edwin Smith. The Egyptology community had heard that he had unusually acquired the Assasif Medical Papyrus.

Though it is questionable whether the Ebers medical papyrus was genuine or a skilled fake, Georg Ebers purchased the Assasif papyrus and proceeded to transcribe one of the most significant medical manuscripts ever written.

Ebers published the medical papyrus as a two-volume color picture reproduction with a hieroglyphic English to Latin translation. Soon after its publication in 1890, Joachim’s German translation appeared, followed by H. Wreszinski’s translation of the hieratic into hieroglyphics in 1917.

Despite repeated attempts to correctly translate the Ebers Papyrus, even the most seasoned Egyptologists have been unable to do so. In the last 200 years, many treatments have been discovered from what has been translated, providing insight into ancient Egyptian civilization.

What have we learned from the Ebers Papyrus?

Ebers published the medical papyrus as a two-volume color picture reproduction with a hieroglyphic English to Latin translation. Soon after its publication in 1890, Joachim’s German translation appeared, followed by H. Wreszinski’s translation of the hieratic into hieroglyphics in 1917.

Carl Von Klein completed the first English translation of the Ebers Papyrus in 1905, Cyril P. Byron completed the second in 1930, Bendis Ebbel completed the third in 1937, and physician and scholar Paul Ghalioungui wrote the fourth. Ghalioungui’s copy of the papyrus is still the complete modern translation. It’s also considered one of the essential works on the Ebers Papyrus.

There are 108 columns in the Ebers Papyrus, numbered 1–110. There are 20 to 22 lines of text in each column. The text concludes with a calendar inscribed in the ninth year of Amenophis I, indicating that it was written in 1536 BC.

It’s chock-full of anatomy and physiology, toxicity, spells, and diabetic care. Animal-borne infections, plant irritants, and mineral toxins are only a few of the therapies covered in the book.

The majority of the papyrus is devoted to healing by applying poultices, lotions, and other medical treatments. It has 842 pages of pharmacological treatments and prescriptions that can be mixed and matched to create 328 combinations for different conditions. However, there is little to no evidence that tested these mixes before the medication. Some believe that certain elements’ associations with the gods prompted such combinations.

According to archaeological, historical, and medical evidence, Ancient Egyptian doctors had the knowledge and talents to treat their patients logically (treatments based on modern scientific principles). It’s possible, though, that the desire to combine magical and religious rites (irrational means) was a cultural demand. If the practical applications failed, ancient medical doctors could always turn to metaphysical explanations for why treatment was not working. A translation of a typical cold healing spell provides an example:

“Fetid nose, fetid nose, fetid nose, fetid nose, fetid nose, fetid nose, fetid nose, fetid nose, fetid Flow out, you who shatter bones, obliterate the skull, and infect the seven holes in the head!” (Line 763) Ebers Papyrus

The heart and cardiovascular system were essential to the ancient Egyptians. They believed that the soul controlled and transmitted bodily fluids such as blood, tears, urine, and sperm. The “book of hearts” section of the Ebers Papyrus describes the blood supply and arteries that connect every part of the human body. Mental issues such as depression and dementia are frequently mentioned as severe side effects of having a weak heart.

Gastritis, pregnancy detection, gynecology, contraception, parasites, eye difficulties, skin disorders, surgical treatment of malignant tumors, and bone setting are all covered in the papyrus.

Most academics feel that one specific phrase in the papyrus’ discussion of various ailments is an exact indication of recognizing diabetes. For example, rubric 197 of the Ebers Papyrus matched the symptoms of diabetic Mellitus, according to Bendix Eb bell. The following is his translation of Ebers’ text:

“If you investigate somebody else sick in the center of his being (and) his body is shrunk down with disease at its limit; if you do not examine him and you do find a condition in (his body except for the surface of his ribs of which the members are like a pill, you must rehearse -a spell- against disease this in your house; you also should start preparing for him ingredients for trying to treat it: floor gargantuan bloodstone; red grain; carob; cook in oil and honey; should eat it (Ebers Papyrus, Rubric No. 197, Column 39, Line 7, Ebers Papyrus, Ebers Papyrus, Ebers Papyrus, Ebers Papyrus, E.

Though parts of the Ebers Papyrus read like mystical poetry, they also reflect the first attempts at diagnosis compared to those seen in modern medical texts. Like many other papyri, the Ebers Papyrus should be understood as practical instruction appropriate to ancient Egyptian society and period, rather than theoretical prayers. These texts served as medicinal cures for diseases and injuries when human misery was thought to be caused by the gods.

The Ebers Papyrus contributes much to our understanding of ancient Egyptian life. If not for the Ebers Papyrus and other texts, scientists and historians would only have mummies, art, and tombs with to work. These artifacts may aid empirical facts, but without written documentation of their version of medicine in the world, there would be no reference for the ancient Egyptian world’s explanation. The paper, however, remains a source of suspicion.

The uncertainty

Given the countless attempts to translate the Ebers Papyrus since its discovery, it has long been assumed that most of its words were misconstrued due to each translator’s prejudice.

Rosalie David, head of the KNH Center for biological Egyptology at the University of Manchester, believes the Ebers Papyrus may be useless. In a 2008 Lancet paper, Rosalie wrote that investigating Egyptian papyri was limited and challenging because of the exceedingly small fraction of work that is assumed to have remained constant across 3,000 years of civilization.

David notes that the terminology in the papers has caused problems for present translators. She also points out that identifying terms and translations in one book frequently contradicts the translated inscriptions in other manuscripts.

Translations, in her opinion, should be exploratory rather than definitive. Because of the difficulties outlined by Rosalie David, most researchers have concentrated on studying individual mummified skeleton remains.

Anatomical and radiological examinations of Egyptian mummies, on the other hand, have shown more evidence that ancient Egyptian physicians were highly proficient. These investigations revealed mended fractures and amputations, demonstrating old Egyptian surgeons’ surgical and amputation abilities. According to research, the ancient Egyptians were also capable of making enormous prosthetic toes.

Mummified tissue, bone, hair, and tooth samples were investigated using histology, immunology, enzyme-linked immunoassay, and DNA analysis. These tests helped to identify ailments that affected the mummified people. Specific disorders found in the mummies were treated using pharmacological treatments described in medical papyri. They indicated that some, if not all, of the medicines listed in documents like the Ebers Papyrus, were effective.

The Ebers Papyrus, for example, provides evidence for the origins of Egyptian medical and scientific literature. In her World Neurosurgery paper, Veronica M. Pagan states:

“These scrolls were likely maintained on hand throughout wartime and utilized as a reference in everyday life to pass along information from generation to generation. Even with these amazing scrolls, it’s likely that medical knowledge was passed down verbally from master to pupil to some extent.” 2011 (Pagan)

Further study of the Ebers Papyrus and the many others that survive aids academics in understanding the relationship between spiritual and scientific knowledge in early ancient Egyptian medicine. It allows one to absorb the tremendous amount of scientific expertise previously known and passed down through generations. It would be easy to forget about the past and assume that we invented everything new in the twenty-first century, but this isn’t always the case.