A three-year-old kid who died around 78,000 years ago is buried in Africa’s earliest known burial. The discovery sheds light on how locals dealt with their deceased at the time.

In Kenya’s Panga ya Saidi cave, archaeologists uncovered the top of a bundle of bones in 2017.

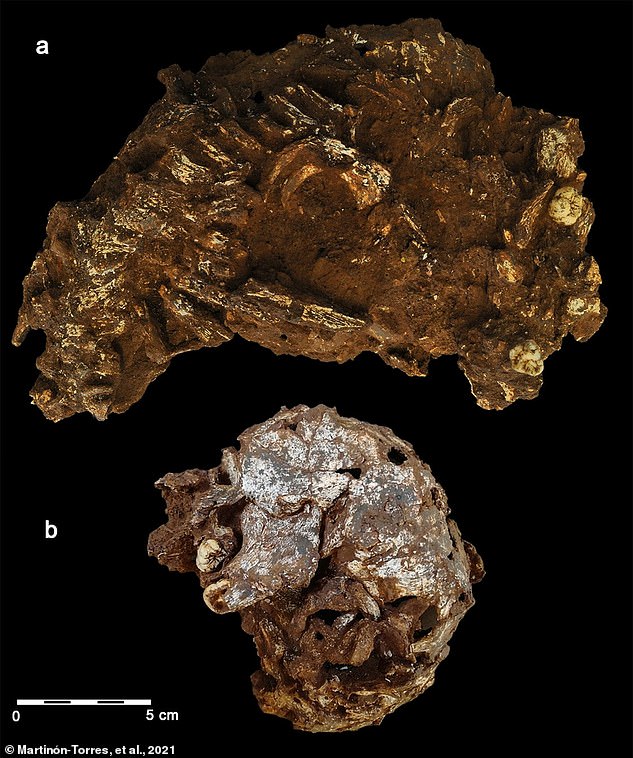

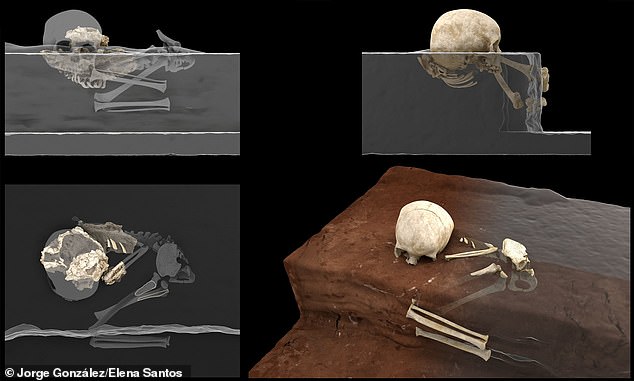

The bones were so delicate that a block of silt around them was removed in its entirety and transferred to Spain’s National Research Centre on Human Evolution (CENIEH), where a meticulous forensic study was carried out.

“We didn’t know what was actually going on in there until a year later,” explains CENIEH researcher Mara Martinón-Torres. “Surprisingly, the sediment block was harboring a child’s body.”

The infant was called Mtoto, which means “child” in Swahili, and the researchers believe they lived about 78,300 years ago, making this Africa’s earliest intentional burial. Martinón-Torres explains, “It was a child, and someone said goodbye to it.”

The youngster had been deposited in an intentionally created hole and covered with cave floor silt, according to an analysis of the dirt surrounding the bones.

Their legs had been dragged up to their chest and they had been positioned on their side. With the exception of a few crucial bones, most of Mtoto’s bones stayed in force as his body disintegrated

The collarbone and upper two ribs were dislocated in the manner of a corpse wrapped in a shroud. Mtoto’s head was tilted in the manner of a corpse whose head had been laid on a cushion. This suggests a planned burial, which might be difficult to show from archaeological evidence.

“The work we’ve done has allowed us to reconstruct the human behavior around the moment the corpse was deposited in the pit,” Francesco d’Errico of the University of Bordeaux, France, explains.

“The writers did an outstanding job of demonstrating that this was a planned burial.”

They’ve lifted the bar and, in my opinion, established the benchmark for what should be done scientifically to indicate purposeful burial,” says Eleanor Scerri of Germany’s Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, who wasn’t involved in the study.

In and of itself, the finding of any ancient human remains in Africa is significant. “Human fossils are uncommon in Africa. “This discovery is highly important since we have massive temporal and geographical gaps,” Scerri explains.

Mtoto was buried during the Middle Stone Age, which lasted around 300,000 to 30,000 years and saw the emergence of a number of contemporary human inventions in Africa. In Africa, early evidence of graves is uncommon.

Although a newborn was buried in Border cave in South Africa approximately 74,000 years ago, and a youngster of 9 years old was buried in Taramsa Hill in Egypt around 69,000 years ago, no buried adults have been discovered during this time.

“I find it extremely remarkable that we had two or three youngsters interred in Africa around the same time,” says Paul Pettitt of the University of Durham in the United Kingdom.

“Mtoto’s burial is an extraordinarily early example of a highly rare treatment of the deceased, which may be typical in the present world, but was rare, unique, and presumably characterized peculiar deaths throughout our species’ early past.”

This paucity of burials indicates that modern human funerary traditions in Africa diverged from those of Neanderthals and modern humans in Eurasia, who began burying their dead around 120,000 years ago.

“That’s rather a contradiction,” d’Errico comments. “These contemporary humans wait a long time to build primary graves in Africa, where we find the origins of symbolic behavior in the form of beads and abstract carvings.”