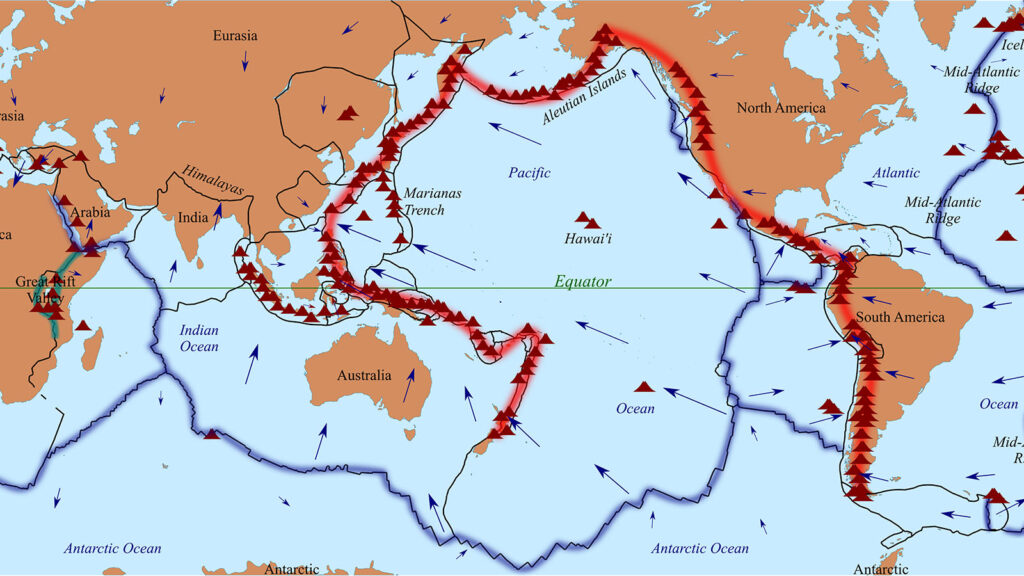

The Pacific Plate is a titan among tectonic plates, covering more than one-third of the Earth’s surface and moving northwest at an astonishing rate of up to 11 centimeters per year.

However, recent observations have shattered this long-held belief, revealing a much more complex and unstable reality lurking beneath the ocean’s surface.

The first signs of trouble appeared subtly, with small but measurable deformations detected in areas of the seafloor that were once considered stable.

Earthquakes began to strike in the heart of the Pacific Plate, far from any plate boundary, raising eyebrows among scientists.

These weren’t the massive quakes that could level cities; rather, they were moderate tremors occurring in unexpected locations, suggesting that the plate might not be a single solid entity after all.

Instead, it could be a colossal puzzle, riddled with hidden fractures both ancient and newly formed.

As researchers delved deeper into these intraplate quakes, they discovered a startling connection to volcanic activity.

Many of these quakes clustered around hot spots—areas where plumes of magma push their way up from the mantle, penetrating the Pacific Plate like a blowtorch through steel.

The Hawaiian Islands serve as a prime example of this phenomenon.

Each island in the chain represents a moment in time, formed as the plate drifted over a stationary hot spot.

However, every eruption required the lithosphere to crack, allowing magma to break through rock once thought unbreakable.

The evidence of instability doesn’t stop there.

Scientists have identified entire fragments of the Pacific Plate breaking off, creating what are now referred to as micro plates.

These micro plates often emerge at complex intersections known as triple junctions, where spreading ridges and transform faults converge.

As the Pacific Plate continues to surge forward, stress accumulates at these weak points, leading to the literal cracking apart of the crust.

This scenario is not without historical precedent.

The Feralon Plate, which once stretched across much of the eastern Pacific, serves as a cautionary tale.

Over time, this massive plate was forced beneath the Americas, disappearing piece by piece until only fragments remained.

Today, those remnants exist as the Cocoos, Naza, and Juan de Fuca plates.

The Juan de Fuca Plate, in particular, poses a significant risk, as it slowly slides beneath North America along the Cascadia subduction zone—a fault line capable of producing one of the most powerful earthquakes on the planet.

The implications of the Pacific Plate’s potential collapse are staggering.

If it begins to splinter, the consequences could be catastrophic for the hundreds of millions of people living along its edges.

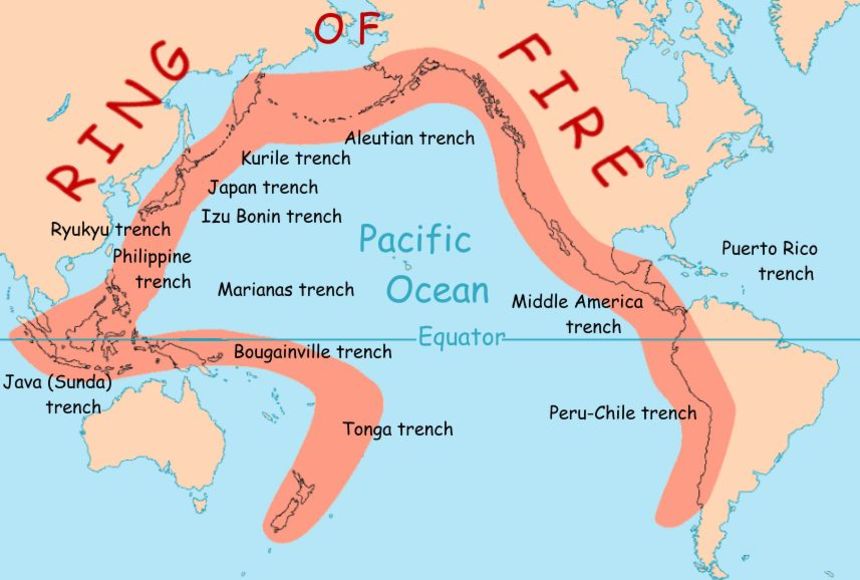

This region, known as the Ring of Fire, is already the most active seismic zone on Earth, stretching from Japan and the Philippines through Indonesia and New Zealand to Chile, Mexico, and the west coast of North America.

With over 800 million people residing in these areas, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

If the Pacific Plate is truly cracking internally, the danger escalates further.

Stresses within the plate could redistribute strain along its edges, triggering larger-than-expected earthquakes and reawakening dormant volcanic arcs.

Zones already primed for disaster, such as Cascadia in the Pacific Northwest, Japan’s Nankai Trough, and the Chilean trench, could see their risk levels rise dramatically.

Each of these regions has the potential to produce magnitude 9 earthquakes, sending tsunamis that could cross entire oceans.

So, what does the future hold for the Pacific Plate? Some scientists speculate that it could eventually split into two or more massive plates, divided along the weaknesses that are already forming in the South Pacific.

Others argue that it will gradually shrink, consumed at its edges by subduction processes.

In the most extreme scenarios, cracks deep within the plate could evolve into entirely new spreading centers, creating new ocean basins.

These theories may sound like distant science fiction, unfolding over tens of millions of years, but the unsettling truth is that the first signs of this future may already be visible today.

The micro plates breaking free in the South Pacific, the volcanic scars left by hot spots like Hawaii and Samoa, and the earthquakes occurring in the middle of the ocean all point to a significant and unsettling possibility: the Pacific Plate has already begun to change.

From a human perspective, the real question isn’t what will happen in 50 million years; it’s what could happen in the next 50 or even the next five.

If internal stresses are shifting within the plate, they could destabilize some of the most dangerous subduction zones on the planet.

The Cascadia subduction zone, the Nankai Trough in Japan, and the Chilean trench are all ticking time bombs capable of unleashing catastrophic earthquakes and tsunamis.

History serves as a stark reminder of the potential devastation.

The Cascadia subduction zone last ruptured in the year 1700, sending a tsunami all the way to Japan.

Chile’s 1960 earthquake, the strongest in recorded history, reached a magnitude of 9.

5, while Japan’s Tohoku earthquake in 2011 unleashed a tsunami that devastated Fukushima and reverberated across the Pacific.

Each of these disasters was triggered at the plate’s edges.

Imagine the repercussions if the stresses within the plate itself begin to feed into those same fault lines.

The instability of the Pacific Plate is both a warning and a challenge.

It serves as a reminder that even the largest geological structures are not immune to collapse.

Understanding these cracks and tremors is crucial for developing strategies to build safer cities, enhance monitoring systems, and prepare for the challenges that lie ahead.

As we stand on the precipice of a new era of earthquakes and eruptions, the Pacific Plate’s restless nature reminds us that our planet is a dynamic and ever-changing entity.

If you want to stay informed about Earth’s hidden forces, from mega quakes to supervolcanoes, make sure to subscribe and keep your eyes on the seismic horizon—because the story of the Pacific Plate is far from over.