This guide explores the enduring mystery of the Great Sphinx. We examine the mainstream view that Pharaoh Khafre built it around 2500 BCE, then dive deep into the controversial Sphinx theories that challenge this timeline. Discover the evidence for the “water erosion theory” suggesting a 10,000 BCE origin, the debate over the recarved head, the truth about the missing nose, and the search for the mythical “Hall of Records.” This is the ultimate guide to the riddles, facts, and fictions surrounding the world’s most enigmatic statue.

For 4,500 years, a colossal statue with the body of a lion and the head of a human has gazed eternally over the Giza plateau. The Great Sphinx is the world’s largest monolith, a guardian carved from a single, massive limestone bedrock. But its true riddle is not one of words, but of stone, sparking countless Sphinx theories about its true origin and purpose.

Key Takeaways

Orthodox View: Most Egyptologists believe the Sphinx was built by Pharaoh Khafre around 2500 BCE.

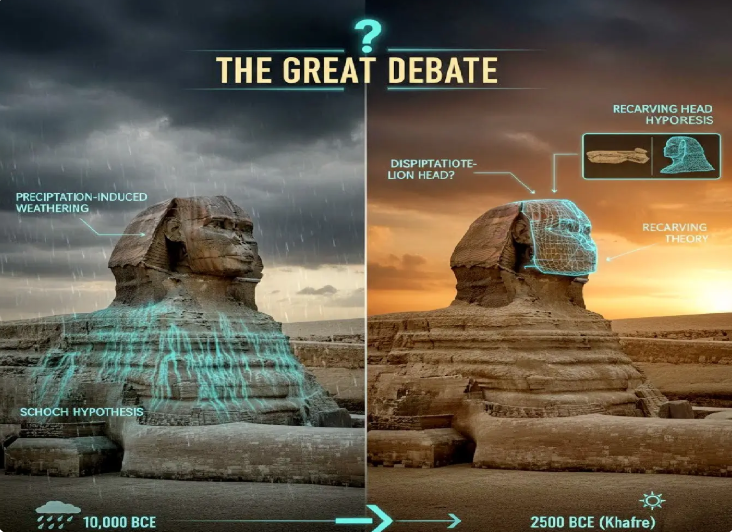

The Core Debate: The “Water Erosion Theory,” championed by Robert Schoch and John Anthony West, suggests the Sphinx is thousands of years older (c. 10,000 BCE).

Key Mysteries: The main debates cover its age, its original form (was the head recarved?), its purpose, and the “Hall of Records” supposedly hidden beneath it.

The Nose: The mystery of the missing nose is solved: It was not Napoleon.

Before we dive into the more controversial Sphinx theories, we must first establish the mainstream archaeological perspective. Most Egyptologists offer a clear, logical answer to the Sphinx’s origin, placing it firmly within the context of the Old Kingdom.

Who Built It?

Mainstream consensus attributes the construction of the Great Sphinx to Pharaoh Khafre (also known as Chephren). He belonged to the 4th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, and his reign dates to approximately 2500 BCE.

What is the Evidence for Khafre?

Archaeologists present several key pieces of evidence supporting Khafre’s connection to the Sphinx:

Proximity and Alignment: The Sphinx stands as a central, integral part of Khafre’s pyramid complex. It aligns perfectly with his causeway and his Valley Temple. Indeed, its very presence makes sense as a guardian figure for his monumental funerary structures.

Stylistic Evidence: The nemes headdress and the royal cobra (uraeus) on the Sphinx’s brow (though heavily damaged) display stylistic features typical of the 4th Dynasty. Furthermore, these elements directly match artifacts associated with Khafre’s reign.

Facial Resemblance: Many experts argue the facial structure of the Sphinx, despite its severe erosion, bears a striking resemblance to known statues of Khafre. They believe the pharaoh commissioned the Sphinx’s face in his own image, representing himself as the solar deity.

The “Dream Stele”: Pharaoh Thutmose IV (who reigned around 1400 BCE, nearly 1,000 years after Khafre) erected a stele between the Sphinx’s paws. This “Dream Stele” describes Thutmose IV’s dream, where the Sphinx (then buried largely by sand) promised him the throne if he cleared the sand. Crucially, the stele contains the name of Khafre. However, the interpretation of this text remains a point of minor contention among Sphinx theories; some argue it merely acknowledges Khafre’s connection to the area, not necessarily direct construction.

What Was Its Purpose?

According to the orthodox view, Khafre intended the Sphinx to serve as a formidable guardian figure. It symbolized colossal royal power and divine protection for his burial complex. Furthermore, they believed it represented the pharaoh himself as the god Horemakhet (“Horus in the Horizon”), an embodiment of the rising sun and a protector of the sacred plateau.

This is the central mystery, the core of all modern Sphinx theories. While the orthodox view presents a neat package, it faces a major challenge—one that comes not from archaeology, but from geology.

The Water Erosion Theory (The “Schoch Hypothesis”)

In the late 1980s, the independent researcher John Anthony West challenged the 2500 BCE date. He saw what he believed was clear evidence of water erosion on the Sphinx’s body, which would be impossible in the Giza desert’s climate for the past 4,500 years.

To test this, West brought in Dr. Robert Schoch, a geologist and professor from Boston University. Schoch, a scientist with no prior investment in alternative history, conducted a formal geological analysis in the early 1990s.

His conclusions ignited the debate:

Here is his core argument: Schoch observed that the deep, vertical, fissured erosion patterns on the Sphinx’s body and, crucially, on the enclosure walls, do not match the horizontal, wind-and-sand erosion that appears on other Old Kingdom structures on the same plateau.

His proposed cause: He argued these patterns are classic examples of precipitation-induced weathering. In simple terms, millennia of heavy rainfall caused this erosion.

Why This Matters: The Giza plateau has been an arid desert since before 2500 BCE. For this much rain erosion to occur, Schoch argued the Sphinx must date to a much wetter period. This points to the end of the last Ice Age, a time between 10,000 and 5,000 BCE.

This theory, if true, would mean the Sphinx is thousands of years older than the pyramids and would force us to rethink the very timeline of human civilization.

The Orthodox Rebuttal (The Counter-Arguments)

Naturally, the scientific and Egyptological mainstream strongly rejects this. Leading experts on Giza, particularly Dr. Mark Lehner and Dr. Zahi Hawass, provide powerful counter-arguments.

They argue that Schoch’s analysis is flawed and that the erosion can be explained by other causes:

Poor Quality Stone: First, they point out that the Sphinx is not a uniform monolith. Its body is carved from poor-quality, layered limestone that is notoriously soft and flaky. This “Member II” limestone is highly susceptible to any kind of erosion, making it a poor candidate for dating.

Haloclasty: Second, they propose that salt crystals caused the damage. They argue that moisture from the air and ground seepage (especially from the Nile floods) wicks into the stone. When this water evaporates, it leaves behind salt crystals. These crystals grow and expand, exerting pressure that flakes and breaks the rock apart, a process which could mimic water erosion.

Capillary Action: Furthermore, they suggest that groundwater wicking up from the bedrock (capillary action) and frequent desert dew could be the source of the moisture, not ancient rain falling down.

Archaeological Silence: Finally, and most powerfully, they ask: If a civilization in 10,000 BCE could engineer the largest statue on Earth, where is all their other stuff? There is zero supporting archaeological evidence—no pottery, no towns, no complex burials, no tools—from that period to suggest a society capable of such a massive project.

The Head-to-Body Ratio: The “Recarving” Theory

This geological debate leads directly to another key mystery—the Sphinx’s head. Look at any picture, and you will notice the head is famously and disproportionately too small for its massive lion body.

This has led to a compelling “recarving theory” that bridges the gap between the other Sphinx theories:

The Theory: This suggests the Sphinx is indeed ancient (perhaps 10,000 BCE) but that its original head was not human. It was likely a lion’s head, in proportion with its lion body, perhaps gazing at its celestial counterpart, the constellation Leo.

Khafre’s Role: Millennia later, around 2500 BCE, Pharaoh Khafre “discovered” this ancient, heavily eroded statue. He then simply re-carved the damaged, ancient lion head into the smaller, human head of a pharaoh—his own.

This single theory cleverly explains two key problems:

It explains why the head is so small (Khafre was limited by the size of the eroded original).

It explains why the head is in much better condition than the body (it’s “newer,” and carved from harder limestone).