The evidence of Petro Zailenko’s quiet legacy can be found all over this corner of the Northern California redwood forest. Signs throughout Hendy Woods State Park, nestled deep in Mendocino County’s Anderson Valley along the Navarro River, bear his name and facts — or theories, at least — about him. They say he was a Russian immigrant born in 1914 who may have been wounded and captured by Nazis during World War II. They say that in the late 1950s or early 1960s, he jumped ship from a Russian fishing trawler in San Francisco and made his way north to Anderson Valley.

According to state park literature, “Nearly all of what we know about Petro Zailenko comes from the encounters of visitors and some locals.” These days, ranger Julie Winchester is the go-to Zailenko historian. She’s worked in Hendy Woods State Park for over a decade and fields the occasional question about the park’s most mysterious resident, in addition to her duties welcoming visitors and describing trails. One late May morning, she directed SFGATE to the Hermit Hut Trail, a short hike to the preserved remnants of Zailenko’s forest shelters.

About a mile down a winding park road and a third of a mile into Hermit Hut Trail, the first of the huts appears. The shelter is a crude lean-to — just strips of redwood bark and sticks propped against a fallen log smoothed by decades of wind and rain. The hollow beneath is just large enough for a man and a few belongings.

A short walk deeper into the grove reveals the second structure, more striking in form. Towering over 10 feet high, the round lodge resembles a rustic tipi, tall enough to stand inside, with a central hearth for fire. Though weathered, it still stands, more than four decades after Zailenko inhabited it.

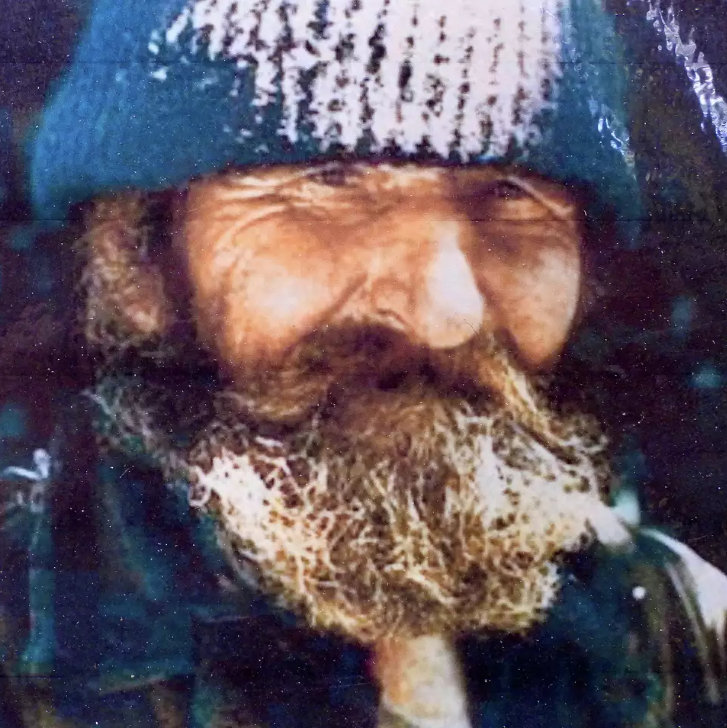

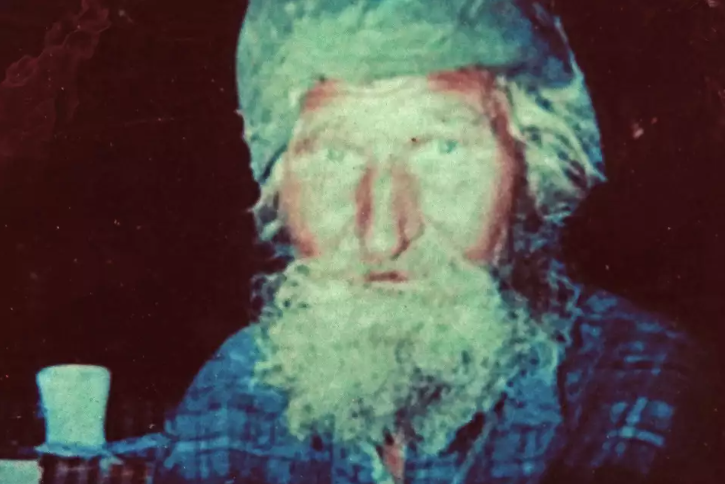

Zailenko, park literature says, stood about 5 foot, 7 inches and weighed less than 100 pounds. He had a long beard and dark eyes and wore mismatched clothes collected from campers, which he refashioned to fit his thin frame. He foraged in nearby gardens, gathered fruit from a commercial orchard across the Navarro River and accepted food from park visitors.

Some referred to Zailenko as “the Mad Russian,” while others called him “a bogeyman,” likely because of his tendency to appear suddenly and startle unsuspecting campers. However, he was never menacing, with park posters describing him as “elusive, harmless, and not considered a threat” — a presence consistent with his quiet, hermetic way of life. He was known to quietly wander into campsites, rubbing his fingers together in a silent request for matches or tobacco. Winchester told SFGATE that many campers remembered him joining their fires.

In August 1981, Zailenko collapsed in a picnic area. He was unable to eat due to intense stomach pain. Rangers took him to a hospital in Ukiah.

Phoenix Winters, an assistant archivist at the Historical Society of Mendocino County, told SFGATE that only one item could be found in the museum’s archives regarding the hermit: a mortuary record confirming he died on Aug. 31, 1981. The hermit was cremated.

The exhibit is quiet, a little dusty and easy to miss. But 44 years after Zailenko’s death, the huts he built still stand, his story continues to be shared from ranger to visitor, and the traces he left behind remain part of the park’s living memory.