Scientists have long believed that Fibonacci spirals are an ancient and highly conserved feature in plants. But, a new study challenges this belief.

The existence of plants can be traced back to roughly 470 million years ago. They manifest in a multitude of patterns, such as the layout of their leaves, the way their branches grow, and the symmetry of their flowers. However, one pattern has particularly perplexed scientists.

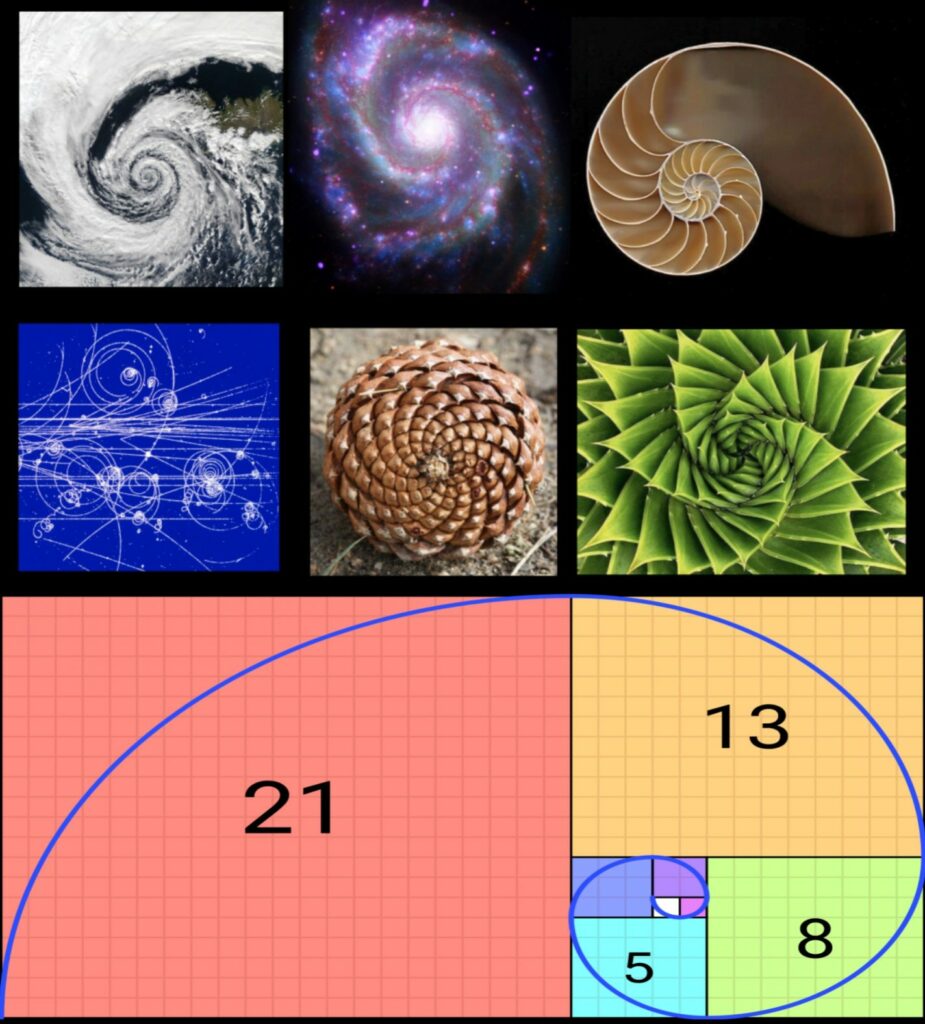

Spirals known as Fibonacci spirals are a unique pattern frequently seen in nature, and predominantly in plants. This pattern was named after Leonardo Fibonacci, an Italian mathematician who introduced the Fibonacci sequence during the 13th century.

For a long time, scientists have held the belief that Fibonacci spirals are a primitive and highly preserved trait in plants. Nonetheless, a recent study published in the journal Science disputes this long-held idea.

The findings indicate that the arrangement of leaves into distinctive spirals, that are common in nature today, were not common in the most ancient land plants that first populated the Earth’s surface.

Instead, the ancient plants were found to have another type of spiral. This negates a long-held theory about the evolution of plant leaf spirals, indicating that they evolved down two separate evolutionary paths.

Whether it is the vast swirl of a hurricane or the intricate spirals of the DNA double-helix, spirals are common in nature and most can be described by the famous mathematical series the Fibonacci sequence; which forms the basis of many of nature’s most efficient and stunning patterns.

Spirals are common in plants, with Fibonacci spirals making up over 90% of the spirals. Sunflower heads, pinecones, pineapples, and succulent houseplants all include these distinctive spirals in their flower petals, leaves, or seeds.

Why Fibonacci spirals, also known as nature’s secret code, are so common in plants has perplexed scientists for centuries, but their evolutionary origin has been largely overlooked.

Based on their widespread distribution it has long been assumed that Fibonacci spirals were an ancient feature that evolved in the earliest land plants and became highly conserved in plants.

Now, an international team led by the University of Edinburgh including University College Cork (UCC) Holly-Anne Turner and researchers at University Münster, Germany, and Northern Rogue Studios, U.K., has overthrown this theory with the discovery of non-Fibonacci spirals in a 407-million-year-old plant fossil.

“The clubmoss Asteroxylon mackiei is one of the earliest examples of a plant with leaves in the fossil record. Using these reconstructions we have been able to track individual spirals of leaves around the stems of these 407-million-year-old fossil plants. Our analysis of leaf arrangement in Asteroxylon shows that very early clubmosses developed non-Fibonacci spiral patterns” stated Holly-Anne Turner.

Using digital reconstruction techniques the researchers produced the first 3D models of leafy shoots in the fossil clubmoss Asteroxylon mackiei – a member of the earliest group of leafy plants.

The exceptionally preserved fossil was found in the famous fossil site the Rhynie chert, a Scottish sedimentary deposit near the Aberdeenshire village of Rhynie.

The site contains evidence of some of the planet’s earliest ecosystems – when land plants first evolved and gradually started to cover the Earth’s rocky surface making it habitable.

The findings revealed that leaves and reproductive structures in Asteroxylon mackiei, were most commonly arranged in non-Fibonacci spirals that are rare in plants today.

This transforms scientists understanding of Fibonacci spirals in land plants. It indicates that non-Fibonacci spirals were common in ancient clubmosses and that the evolution of leaf spirals diverged into two separate paths.

The leaves of ancient clubmosses had an entirely distinct evolutionary history from the other major groups of plants today such as ferns, conifers, and flowering plants.

The team created the 3D model of Asteroxylon mackiei, which has been extinct for over 400 million years, by working with digital artist Matt Humpage, using digital rendering and 3D printing.