Divers have discovered the oldest Swedish cog ship, as well as one of the oldest cog shipwrecks ever discovered in European seas, in the region of Bohuslän. The wreck of the Swedish cog ship was discovered off the shore of Dyngö, a small island off the coast of Fjällbacka, a historic fishing community and famous tourist destination on the west coast of Sweden. The settlement gets its name from a massive rock, or “mountain,” that dominates the harbor and welcomes sailors arriving from the open sea. The discovery was made public in a recent study article published in PHYS.

Ancient Tree Rings Reverse Engineered

Professor Staffan von Arbin of the University of Gothenburg is a marine archaeologist who just released a study paper in PHYS on the finding of the Swedish cog ship disaster.

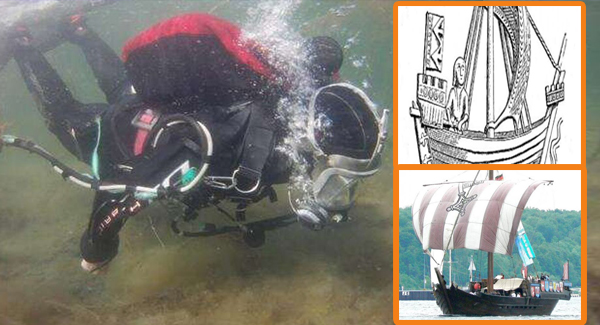

Teams of divers and archaeologists from the University of Gothenburg performed reconnaissance along the coast of Bohuslän in September and discovered the wreck. Dendrochronology (the study of tree rings) indicated that the wooden hull’s samples were oak beams cut between 1233 and 1240 AD, putting the ship’s age at approximately 800 years.

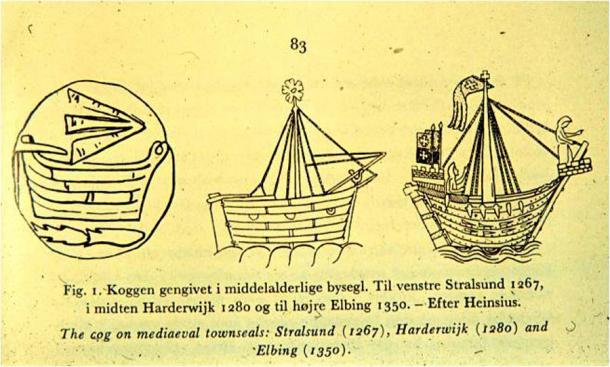

The mystery ship has been dubbed “Dyngökoggen” by marine archaeologists, and it has been proven that it is a cog ship, which was widely employed across Sweden (and on German Baltic Sea trade routes) from the early 12th century onwards, according to Staffan von Arbin. The Swedish cog ship’s seams between the wooden planks were found to be sealed with moss, which is a common design element for 13th-century cogs. The ship’s surviving piece is around 10 meters (33 feet) long and 5 meters (16.5 feet) broad, although it was once about 20 meters (66 feet) long, according to Staffan von Arbin.

The wood samples recovered from the Swedish cog disaster proved that the ship was not only composed of oak but that the oak lumber originated from northwest Germany.

During the great herring time of the 1750s, Fjällbacka grew into a resort, and by the mid-nineteenth century, it was Sweden’s most productive fishing community. When early Swedish cogs sailed these waterways 800 years ago, this region was just as bustling.

The Hanseatic League’s Favorite Ship Was The Cog

During the medieval period, cogs were largely involved with seagoing trade in northwest Europe, particularly the Hanseatic League. The length of a typical seagoing cog was around 15 to 25 meters (49 to 82 feet), with a beam of 5 to 8 meters (16 to 26 ft).

For its broad trading lines, the Hanseatic League made great use of cogs. According to a recent study from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, historical documents on the League emphasize “the importance of Bohuslän as a transit route for international marine trade during this period.”

From the period of the Norwegian invasion and unification of the area in the 870s until the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658 AD, Bohuslän was called after the fabled medieval Norwegian fortress of Bohus, which dominated the entirety of this old Norwegian county.

The archaeologists don’t know why the Swedish cog ship sunk, but they believe it was an “interesting narrative” because the ship’s survey displays signs of a large fire.

Perhaps the word “exciting” is a misnomer. Maybe a little dramatic. And unquestionably horrifying. The Dyngökoggen cog ship wreckage is one of the oldest cogs ever unearthed anywhere in Europe, which is very fascinating for Sweden. So, how did this ship travel from the top of the waves in one of the busiest maritime channels in medieval Europe to the bottom of the sea off the coast of Sweden?

Pirates, Fire, and War: How Did The Swedish Cog Fall Apart?

Professor von Arbin speculated that the ship had been “assaulted by pirates.” This theory is based on ancient documents that mention “strong pirate activity” throughout Norway’s southern coast, including Bohuslän, during the Middle Ages.

Another theory is that the ship sank during a naval battle, as Bohuslän was a battleground in the Norwegian crown’s medieval conflicts. The expert did say, however, that the fire may have been a “simple accident,” and that it could have spread while the ship was docked.

Divers will not be returning to this wreck shortly due to a lack of money for this sort of study. They do know, however, that Dyngökoggen is simply one of many such shipwrecks on what was once a historic European trade route, another of the ghost ships that drowned in the service of enriching the Norwegian crown.