The Ethiopian Bible, also known as the Orthodox Tewahedo Bible, holds profound significance for certain communities, carrying a weight comparable to other religious texts. This ancient scripture, with its unique narratives and historical context, offers a fascinating glimpse into Ethiopia’s Christian heritage and its enduring legacy. Below, we explore the captivating stories, historical facts, and possible secrets embedded in this remarkable tome, which has been preserved for centuries.

A Historical Marvel

Approximately 800 years ago, an Ethiopian king commissioned the construction of Lalibela, a new Christian capital renowned for its rock-hewn churches. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church attributes their creation to divine intervention, claiming angels crafted these sacred spaces. Meanwhile, a secluded Ethiopian monastery guards profound secrets about humanity, with worshippers revering their enigmatic book as their Bible. Surprisingly, the widely accepted King James Bible (KJV), finalized in 1611, marginalized some of the world’s oldest scriptures, including those from Ethiopia, for reasons that continue to intrigue scholars.

Ethiopia: An Early Christian Stronghold

To understand why the Ethiopian Bible is banned in the West, we must delve into the early history of Christianity in Ethiopia. Christianity’s roots in the region trace back to the 4th century AD, when King Ezana of the Aksumite Kingdom embraced the faith, making Ethiopia one of the earliest regions to adopt Christianity. Archaeological evidence, such as the 2019 discovery of a 4th-century Christian church 30 miles northeast of Aksum, confirms Ethiopia’s swift adoption of the faith, coinciding with Emperor Constantine’s legalization of Christianity in the Roman Empire.

Despite this rich history, the Western church does not recognize the Ethiopian Bible as canonical. The Tewahedo Bible differs significantly from the KJV, containing 88 books compared to the KJV’s 66. Unique texts like the Book of Enoch and the Book of Jubilees offer insights into early Jewish thought and Christian theology, absent from Western canons. The Ethiopian Bible’s illustrations and additional books, coupled with its distinct liturgical practices in the ancient Ge’ez language, make it a radical departure from Western Christian traditions.

A Legacy of Independence

Ethiopia’s Christian tradition remained untainted by European colonization, allowing the Tewahedo Bible to retain indigenous characteristics. This independence underscores the scripture’s cultural and spiritual significance. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, predating the Catholic Church, claims a 3,500-year connection to Christianity, with some tribes adopting the faith before it spread widely outside Rome. The church’s syncretism—blending Jewish traditions like Sabbath observance with Christian beliefs—highlights Ethiopia’s complex religious landscape.

The Forbidden Bible’s Secrets

The Ethiopian Bible’s ban in the West may stem from its narratives, which challenge mainstream Christian teachings. Its ancient scrolls, predating the KJV, include stories and teachings absent from other canons, offering an alternative perspective on Christianity. For instance, the Kebra Nagast, Ethiopia’s sacred text, expands on the biblical account of the Queen of Sheba’s visit to King Solomon in the 10th century BC. It claims the queen bore Solomon’s son, Menelik, who became Ethiopia’s king, a detail absent from the Hebrew Bible. Genetic studies since 2012 suggest intermingling between Ethiopians and people from Jerusalem around 3,000 years ago, lending credence to this narrative.

Why the Ban?

The Western rejection of the Ethiopian Bible may be rooted in historical and political factors. The Bible, as we know it, has undergone numerous revisions, with translations like Saint Jerome’s Vulgate (circa 400 AD) shaping the canon. The Council of Nicaea (325 AD) and the First Council of Constantinople (381 AD) established strict criteria for New Testament texts, excluding those not written by Jesus’s direct followers or aligned with accepted scriptures. Ethiopia’s distance from these early Christian centers and its unique texts likely contributed to its exclusion.

King James’s standardization of the Bible in 1611 further marginalized the Ethiopian Bible. His project prioritized texts that reinforced his authority, omitting those deemed noncanonical or lacking popularity. The Ethiopian Bible’s additional texts, often labeled pseudepigraphical, were dismissed by Western denominations as inauthentic, despite their historical significance.

Cultural and Artistic Significance

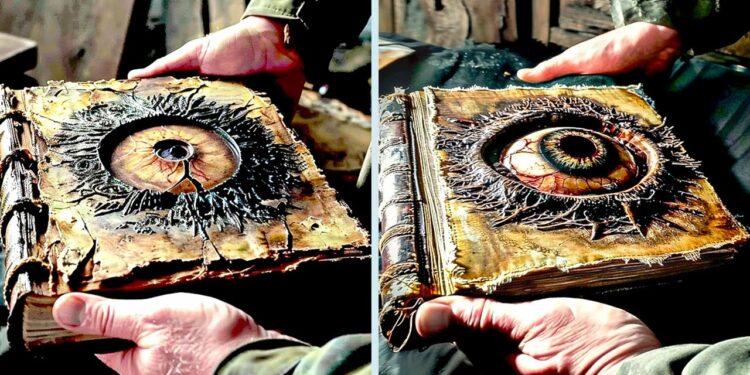

Beyond religion, the Ethiopian Bible shapes Ethiopia’s cultural identity, influencing art, music, and oral storytelling. Its richly illustrated manuscripts, such as a 2010 discovery in a mountaintop monastery, reveal the world’s oldest illustrated scriptures. These texts, written in Ge’ez, visually narrate biblical stories, offering a unique approach to spiritual expression. The church’s vibrant traditions, including fasting, feasting, and celebrating saints, reflect Ethiopia’s rich heritage.

The Queen of Sheba and Beyond

The story of the Queen of Sheba exemplifies the Ethiopian Bible’s divergence from Western narratives. Originating from the Kingdom of Sheba (modern-day Yemen and Ethiopia), she visited Jerusalem to seek wisdom from King Solomon, bringing spices, gold, and precious stones. The Kebra Nagast’s account of her son Menelik challenges the biblical narrative, highlighting Ethiopia’s historical ties to Jerusalem. Archaeological findings in Ethiopia and Yemen confirm ancient trade links, underscoring the region’s role in cultural and religious exchange.

A Call for Reconsideration

The Ethiopian Bible and its scrolls offer a distinct perspective on Christianity, challenging Western interpretations. They remind us of the faith’s diverse roots and the importance of understanding different cultural contexts. By exploring these narratives, we uncover a complex tapestry of faith, culture, and history that transcends borders. The Ethiopian Bible’s exclusion from the Western canon raises questions about inclusivity and the shared heritage of humanity, urging us to reconsider its significance in the global Christian tradition.