There is no place like Earth here, but maybe there was a long time ago.

There is no place like Earth here, but maybe there was a long time ago. On March 27, 1972, the surface of Venus was looked at by Venera-8, a Soviet atmospheric space probe and lander. It was the second spacecraft to land on the planet.

Even though we can’t see the surface of the planet from space, Venera-8 made some surprising discoveries about how visible the surface is and gave important geochemical data that supports the idea that Venus is Earth’s sister planet.

Even though Mars is 34 million miles away, many people think of it as Earth’s younger sister. But Venus is 25 million miles closer to Earth at the point in its orbit where it is closest to our planet. Earth and Venus are about the same size and mass, but Earth is about twice as big as Venus.

Early on, Earth and Venus seem to have been like twin sisters (minus a Venusian moon). NASA scientist Michael Way and his colleagues wrote an article in 2016 about how Venus may have had water until 700 million years ago. If this is true, could the way Venus is now be a sign of how Earth will be in the future?

Space exploration has moved away from Venus, which has a hot, thick atmosphere, and toward Mars, which has a cooler, less dense atmosphere. Since the Soviet Union launched Vega 2 in 1985, no lander has been sent to the surface of Venus. Gregory Shellnutt, a well-known professor of geochemistry at National Taiwan Normal University, says that we seem to have forgotten that “Venus is Earth’s sister in every way. They’re not twin sisters, but they’re sisters.”

With the Venera program, which sent up 28 spacecraft between 1961 and 1983, the Soviet Union moved ahead in the race to get to space. Venera-8 was both the second thing made by humans to land on Venus and the first thing to do so successfully. When Venera-7 was launched two years ago, it was the first time a spacecraft tried to land on another planet and only had some success. But a problem with the lander’s parachute caused it to tumble into free fall, which hurt it badly and stopped it from sending high-quality data continuously.

During the 18-year Venera mission, 13 spacecraft made it into Venus’s atmosphere, and eight of them landed on the planet.

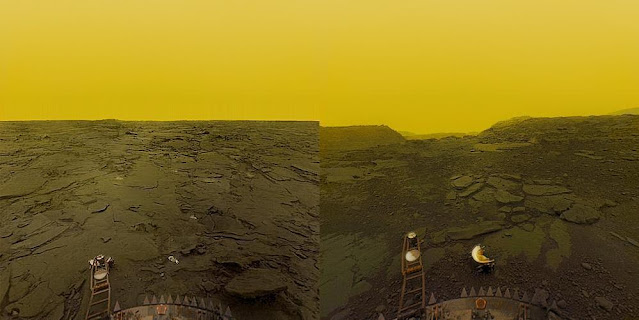

On March 27, 1972, Venera-8 was sent into space to study Venus’s atmosphere and surface. The spaceship took 118 days to get to the planet. A cooling system was built into Venera-8’s descent through the atmosphere to the surface. This was done to make sure that the equipment would last longer. This is because, during the day, the surface temperature of Venus may rise above the melting point of lead (620 degrees Fahrenheit).

Venera-8 had a gamma-ray spectrometer, equipment for analyzing gases, an altimeter, a photometer for measuring light, sensors for measuring pressure and temperature, and a radio transmitter. Venera-8’s job was to make sure that Venera-7’s measurements of Venus’ atmosphere were correct. Despite problems with its landing, Venera-7 was able to record that Venus’ atmosphere is made up of 97 percent carbon dioxide. Also, it found that the surface temperature was 887°F and the pressure was 9.0 MPa (vs. 0.1 MPa on Earth). These observations quickly showed that there is no water on Venus’s surface and that it is not a good place for humans to live.

Venus doesn’t have a magnetic field either, or if it does, it’s not very strong. Shellnutt says this is because the surface of Venus has reached the Curie temperature. The temperature at which a substance stops being magnetic is called its Curie temperature.

Venera-8 confirmed what Venera-7 had found, but because Venera-8 landed so well, its photometer showed something different.

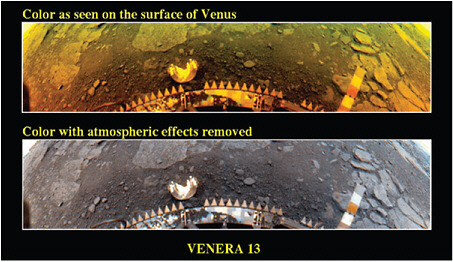

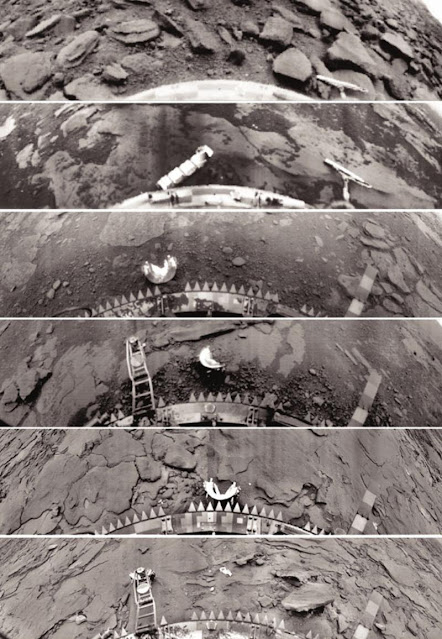

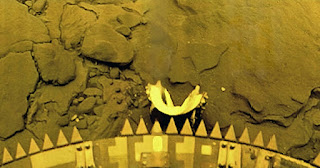

Even though it was hard to see the planet’s surface through Venus’s hazy atmosphere, visibility on the planet’s surface was about the same as on a foggy day on Earth, with about one kilometer of visibility in each direction. Clouds could be seen way up in the sky. Engineers working on the Venera project found out after Venera-8 landed that it would be able to take pictures of the surface. So, when Venera-9 landed successfully in 1975, it was also the first lander to take pictures of the surface of a planet other than Earth.

So, when Venera-9 landed successfully in 1975, it was also the first lander to take pictures of the surface of a planet other than Earth.

Venera-8 lasted less than an hour on the surface of Venus, which is very hot.

During the 50 minutes and 11 seconds after landing, Venera-8 also measured the amounts of thorium, potassium, and uranium in the surface material of Venus. These are trace elements, which means they are found in small amounts on Earth. They can be found in basalts, like those in Hawaii or at mid-ocean ridges.

Shellnutt has been interested in Venus since he was ten years old, and he has watched how the study of Venus has changed over the years. He remembers using crystallization modeling software to look at rocks on Earth. When he found the Venera-8 gamma-ray spectrometer trace element data, he was immediately reminded of all the Venus missions and their geochemical data.

Venera-8 was different from other landers because its data showed a big difference from what other landers had found. Shellnutt says that even with a 30% error margin, Venera-8 found levels of trace elements that were too high to be the same as basalts found along a mid-ocean ridge or in Hawaii. Unlike Venera-8, the other Venus landers found geochemical values that were more like those found in or near a mid-ocean ridge.

“Most of the natural radiation we get comes from the potassium in crystal rocks. The Moon is a good example. Mars is a good example. Shellnutt says, “This is true for any planet with land.”

In a 2019 paper called “The Curious Case of the Venera-8 Rock,” Shellnutt talks about how he used his Earth-based crystallization modeling techniques to figure out that the trace element values at the Venera-8 landing site may be similar to Archean greenstone belts, which are a type of continental crust on Earth. The Archean was a time on Earth between 2.5 billion and 4 billion years ago. Many scientists think that greenstone belts are a type of continental crust that formed chemically from mafic basalts over billions of years.

The Earth looked very different during the Archean. The planet had just been made, so it was extremely hot. Earth’s tectonic regime during this time, as well as Venus’s current and past tectonic regimes, are still unknown because of how hot they are. At the moment, there is no evidence that plate tectonics work on Venus in the same way they do on Earth.

The geography of Venus is also very different from that of Earth. Shellnutt shows the beautiful volcanic mountains and landmasses as big as Africa, but there is one important difference.

“If we look at the Earth during the Archaean, there is a lot of disagreement about whether or not modern plate tectonics worked during that time. So, how do these landforms get there? How does all this bending happen? Compression mountains have been seen on Venus. “There are signs of rifts, so it’s clear that it’s geologically active, but it’s not broken up into plates,” he says.