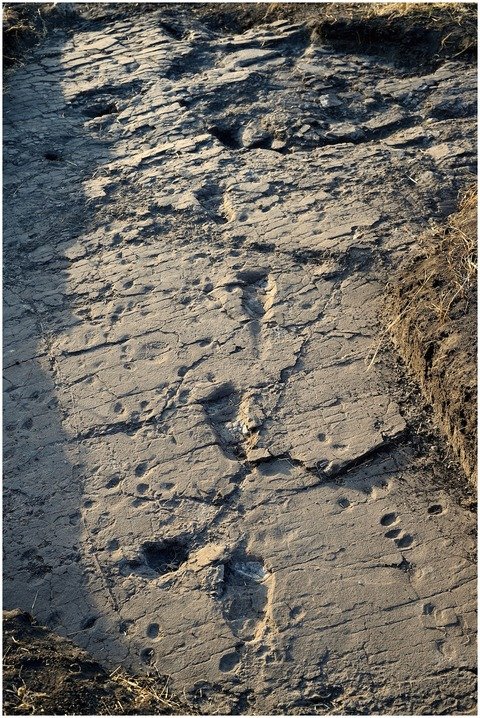

Three has grown to five. The renowned ancient footprints of Laetoli in northern Tanzania capture the moment – 3.66 million years ago – when three members of Lucy’s species (Australopithecus afarensis) marched forth over the landscape.

Something unexpected has been discovered: the footprints of two additional people.

“Our discovery left us without words,”says Marco Cherin of the University of Perugia in Italy.

The discovery appears to have the potential to change our knowledge of the Laetoli site and the social dynamics of australopiths and their walking style.

In 1976, the original Laetoli footprints were uncovered. Nothing like them had ever been discovered before. They are by far the earliest hominin footprints known, having been preserved by a group of australopiths walking on moist volcanic ash during the brief period before it hardened from soft powder to hard rock.

“Geologists say this hardening process must have occurred in just a few hours,” Cherin explains.

Discovered by chance

The new finding happened by luck. To attract visitors, the government requested Fidelis Masao, a scholar at Tanzania’s University of Dar es Salaam, to explore the impact that building activity would have on the site’s important geology, according to Cherin.

Masao and his colleagues excavated around 65 pits to better understand the size of the ash layer in which the footprints were discovered. The other prints were found in one of the trenches, and other archaeologists, including Cherin, proceeded to analyze them.

So far, the researchers have discovered 13 impressions from a huge person known as S1 and a solitary print from a smaller S2 australopith. They estimate that after the entire region has been excavated, there might be up to 50 prints belonging to S1.

S1 appears to have walked in the same direction, at the same pace – and most likely at the same time – as the australopith footprints discovered in the 1970s.

The original trackways – commonly rebuilt as belonging to two adults and one child – have been too tempting to interpret as evidence of an ancient “nuclear family.”

According to the fresh footprints, more adults were present, including one significantly bigger, the S1 person. This has given rise to a new theory concerning the social groupings of Australopiths.

“They were probably similar in certain respects to those of our cousins, the gorillas, with a single dominant big male accompanied by his females and their offspring,” says Giorgio Manzi of Rome’s Sapienza University, who was also involved in the excavations.

However, australopiths may have differed from gorillas in other ways. According to a 201, which can identify where an individual grew up, the smaller (most likely female) australopiths left their family groupings to explore and join a new social group. In contrast, bigger males leave their families in gorillas to form a separate social group.

The modern walk?

The new footprints might also help us decide if the australopiths walked like us, which is a contentious question. Some experts, such as Robin Crompton of the University of Liverpool in the United Kingdom, have researched the Laetoli prints discovered in the 1970s.

According to the researchers, the depth profiles of the prints reveal that australopiths moved in a broadly contemporary manner: the hominins appear to have had a well-developed arch in the foot and utilized their big toe to push off the ground.

Other scholars, notably Kevin Hatala of Chatham University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, have taken a different print approach. Earlier this year, Hatala and his colleagues decided that the australopith walk may have appeared weird to contemporary eyes, with the knees slightly bent as each foot touched the ground.

“A substantially long trackway could prove very informative,”adds Hatala.

One of the fascinating elements of the discoveries, according to Cherin, is the size of the S1 australopith. Its feet were 26 centimeters long, 3.5 centimeters longer than the other Laetoli prints. The experts believe S1 stood 1.65 meters tall, equivalent to current people.

However, William Jungers of Stony Brook University School of Medicine in New York advises us to proceed with care.

Hominin foot bones are highly uncommon in the fossil record, and it’s not apparent that australopiths had feet proportionate to their size as humans do. “Australopiths aren’t modern people in many respects,” he argues.

More information will be released when the researchers return to Laetoli to begin excavations, which might happen as soon as mid-2017.