A 1.5 million-year-old human vertebra discovered in Israel suggests that our ancient relatives migrated from Africa to Eurasia in waves, according to a new study.

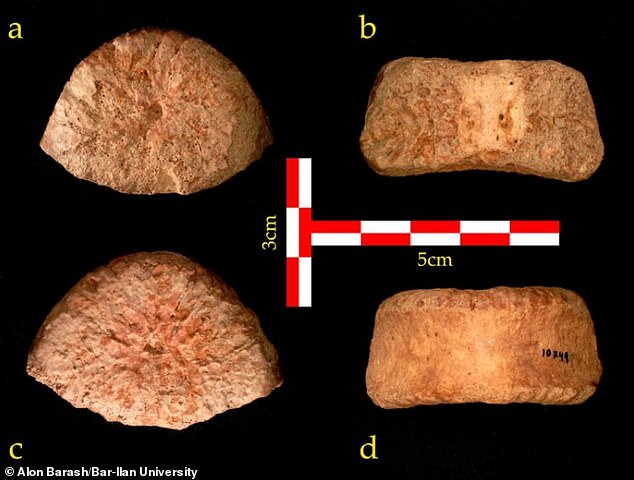

Scientists have analysed the vertebra fossil, referred to as UB 10749, that was unearthed at the archaeological site of Ubeidiya, Jordan Valley, Israel in 1966.

The vertebra likely came from a boy aged between six and 12 years at the time of death, who was tall for his age and could have reached 6.5 foot tall had he survived, the researchers now reveal.

It’s not known how or why he died, but his remains offer the earliest evidence of ancient man discovered in Israel.

Differences in size between the fossil and other finds in Dmanisi, another archaeological site in Georgia, suggest two different hominin populations arrived in Europe from Africa several hundreds of thousands of years apart.

The first wave of ancient human migration reached Georgia approximately 1.8 million years ago, while the second reached Israel 1.5 million years ago.

The new study has been led by researchers at Bar-Ilan University, Ono Academic College, the University of Tulsa and the Israel Antiquities Authority.

A combination of the size of the fossil and the level of ‘ossification’ – the formation of new bone as humans age – allowed them to work out an age at death.

‘We report on the earliest large-bodied hominin remains from the Levantine corridor – a juvenile vertebra (UB 10749) from the Early Pleistocene site of Ubeidiya, Israel, discovered during a reanalysis of the faunal remains,’ the team say in their paper.

‘The vertebra belongs to an individual that had not reached puberty … we estimate that the age at death for UB 10749 is between 6 and 12-years-old.’

The legendary site of Ubeidiya has already been dated to 1.5 million years ago, study author Dr Alon Barash at Bar-Ilan University told MailOnline.

‘This is based on the type of animals who are found there, and some initial dating made a while ago,’ he said.

According to Dr Barash and his fellow experts, ancient human migration from Africa to Eurasia was not a one-time event but occurred in waves.

The experts claim to know this because of ‘paleobiological differences’ between UB 10749 found in Israel and other early remains found at the archaeological site of Dmanisi, Georgia.

These physical differences suggest Ubeidiya and Dmanisi were home to populations of ‘two distinct hominins’ that made their journeys from Africa 200-300 thousand years apart.

People in Ubeidiya were bigger than the short-statured hominins that lived in Georgia, the team claim.

‘The differences are both is size and shape,’ Dr Barash told MailOnline. ‘The Dmanisi vertebra are smaller – the hominins in Georgia are about 1.5 metres [4.9 feet] high and weigh about 35-45 kg.’

The newly-studied vertebra from Ubeidiya, meanwhile, suggests a much bigger human, he said.

In fact, it was only due to the lack of ossification in this vertebra fossil that brought the overall age estimation down to 6-12 years.

Taking into account the vertebra fossil’s size alone suggests an older age, probably between 11 and 15 years, because it is so big.

‘Our vertebra belonged to a child, and the adult size prediction is conservatively about 1.8-2 meters [5.9 to 6.5 feet] and 90-100 kg,’ Dr Barash told MailOnline.

‘Even if this is an adult vertebra (and the level of ossification is of a child) it is still very big. Shape-wise they look different. Dmanisi are more elongated and more round.’

According to already-established fossil evidence and DNA research, human evolution began in Africa about six million years ago.

Approximately two million years ago, ancient humans – nearly but not yet in modern form – began to migrate from Africa and spread throughout Eurasia, a process known as the ‘Out of Africa’.

Ubeidiya, located in the Jordan Valley near the kibbutz of Beit Zera, is one of the places where there is archaeological evidence for this dispersal.

Ubeidiya is the second oldest archaeological site outside Africa (after Dmanisi) and was excavated by several expeditions between 1960 and 1999.

Ubeidiya has also yielded stone and flint artifacts, hand axes made from basalt, chopping tools, and flakes made from flint.

Other finds from Ubeidiya include a rare collection of stone tools and extinct animal bones, from species including the saber-toothed tiger, mammoths and a giant buffalo, alongside animals not found today in Israel, such as baboons, warthogs, hippopotamuses, giraffes and jaguars.

Recently, excavations in Ubeidiya were resumed by Professor Miriam Belmaker of the University of Tulsa and Dr Omry Barzilai of the Israel Antiquities Authority under a US National Science Foundation grant.

The project used new absolute dating methods to refine the site’s dating to 1.5 million years and to study the paleoecology and paleoclimate of the region.

While looking at the fossils from the site, now housed at the Hebrew University’s National Natural History Collections, Professor Belmaker encountered the human vertebra initially unearthed in 1966.

The bone was studied by Dr Barash and Professor Ella Been, who identified it as a human lumbar vertebra. At approximately 1.5 million years old, it’s the earliest fossil evidence of ancient human remains discovered in Israel.

According to Dr Barash, there has been ongoing debate in scientific literature about whether the migration was a one-time event or occurred in several waves, but the new find from Ubeidiya sheds ‘unambiguous evidence’ on this question.

‘Due to the difference in size and shape of the vertebra from Ubeidiya and those found in the Republic of Georgia, we now have unambiguous evidence of the presence of two distinct dispersal waves,’ he said.

As to why the two populations left Africa, researchers think climate was key.

‘One of the main questions regarding the human dispersal from Africa were the ecological conditions that may have facilitated the dispersal,’ Professor Belmaker said.

‘Previous theories debated whether early humans preferred an African savanna or new, more humid woodland habitat.

‘Our new finding of different human species in Dmanisi and Ubeidiya is consistent with our finding that climates also differed between the two sites.

‘Ubeidiya is more humid and compatible with a Mediterranean climate, while Dmanisi is drier with savannah habitat.

‘This study showing two species, each producing a different stone tool culture, is supported by the fact that each population preferred a different environment.’